[HGPI Policy Column] No. 7 – From the Dementia Policy Team

date : 2/12/2020

Tags: Dementia, HGPI Policy Column

![[HGPI Policy Column] No. 7 – From the Dementia Policy Team](https://hgpi.org/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/column-7-top.jpg)

Introduction

In our previous column, we described the current situation surrounding what are known as Blank Periods in Japan.

To review, the two Blank Periods we discussed were:

Blank Period 1: Between the first suspicions of dementia and receiving a differential diagnosis.

Blank Period 2: Between diagnosis and the start of services provided by long-term care insurance.

The study we discussed in our previous column demonstrated that longer period lengths for Blank Period 2 increased the burdens placed on the families of people with dementia. Among current services in Japan, the Initial-phase Intensive Support Team System for Dementia has the potential to provide support during Blank Period 1. We concluded that making substantial, concrete policies for providing support during Blank Period 2 will be a priority issue moving forward.

In this column, we will introduce the Post Diagnostic Support (PDS) system currently being used in Scotland. We believe a PDS system may provide support during Blank Period 2 in Japan. In Scotland, there is a working group called the Scottish Dementia Working Group (SDWG) which was established by people with dementia and is famous for its immediate calls for action from society. The PDS system was created due to demand from the SDWG. The specialists who provide PDS are called Link Workers and interest in the Link Worker system is increasing in Japan. An initiative to train Link Workers is underway in Kyoto and a citizens’ organization in Fukui Prefecture is working to train Link Workers among members of the public.

The fundamental concept behind the PDS system is community development. While many in Japan tend to focus on the PDS system itself, we feel that community development is more important. The PDS system does not only establish specialist positions called “Link Workers.” It also includes significant and comprehensive community-centered efforts towards building a dementia-friendly society. Those efforts revolve around what are known as Resource Centres. As the base for community activities, Resource Centres are where people work to generate community resources needed for daily life after diagnosis and to develop community awareness. In addition to introducing the PDS system and Resource Centres, we will also consider suggestions for Japan we collected by examining dementia policy in Scotland.

The Scottish Government and Scotland’s National Dementia Strategy

Scotland is a country that is part of the United Kingdom together with Great Britain, Wales, and Northern Ireland. It covers the northern region of the island of Great Britain. Like Wales and Northern Ireland, its status is unique owing to the complicated nature of its historical relationships and it is neither entirely dependent or independent as a country. Scottish independence from England is a regular topic of discussion in the country’s political agenda and public votes on Scottish independence have been taken several times. The Scottish National Party (SNP), a political party that supports and campaigns for Scottish independence, made significant progress in December 2019 by winning thirteen seats in the United Kingdom general election, bringing its total number of seats up to 48.

Over 20 years have passed since Scotland established its own parliament in 1999. Aside from reserved matters such as constitution, national security, and foreign policy, the Scottish Parliament can operate independently from England and has the power to act on various matters such as healthcare, welfare, education, and judicial power. It is the body that enacted the Charter of Rights for People with Dementia and their Carers in Scotland in 2009. We introduced the Charter in our second column.

In 2018, Scotland’s population was about 5.4 million people, 19% of which was age 65 and over. There are an estimated 90,000 people with dementia in Scotland. Scotland has created national dementia strategies three times. The current strategy, the Third National Strategy for Dementia, was presented in 2017. While we do not have space to discuss its details here, it is worth noting that it was created through the joint efforts of the Scottish government and Alzheimer Scotland, a dementia support NGO. Through it, revolutionary efforts to unite the government and the public are currently underway.

(Photo: The Scottish Parliament taken by Mr. Kurita in September 2019.)

Introducing the Post Diagnostic Support System

Next, we will introduce Scotland’s PDS system, the main theme of this column. PDS is a public service provided through National Health Service Scotland (NHS Scotland), which provides free healthcare services funded mainly by the public. In the PDS system, after someone who is suspected to have dementia is diagnosed by a medical specialist, they are assigned to a PDS specialist called a Dementia Link Worker.

Link Workers find community resources or other usable services and introduce them to people with dementia to enable them to continue living in their own communities. They also help people with dementia understand and accept dementia. Their advice covers topics like lifestyle planning strategies that take into account the physical and mental changes accompanying the progression of dementia or ways to maintain relationships with friends, family members, and other people.

I have visited Scotland several times to observe their system and interview Link Workers. Support provided by Link Workers is tailored around the needs of the person receiving it to help them understand their situation, envision their own future lifestyle, and enable them to make decisions independently. With these goals in mind, support is provided as required by the situation of the person with dementia or their family.

Currently, there are 76 Link Workers at Alzheimer Scotland. Each Link Worker supports about 50 to 70 people. Some Link Workers are full-time specialists and some belong to the NHS where they may have other roles.

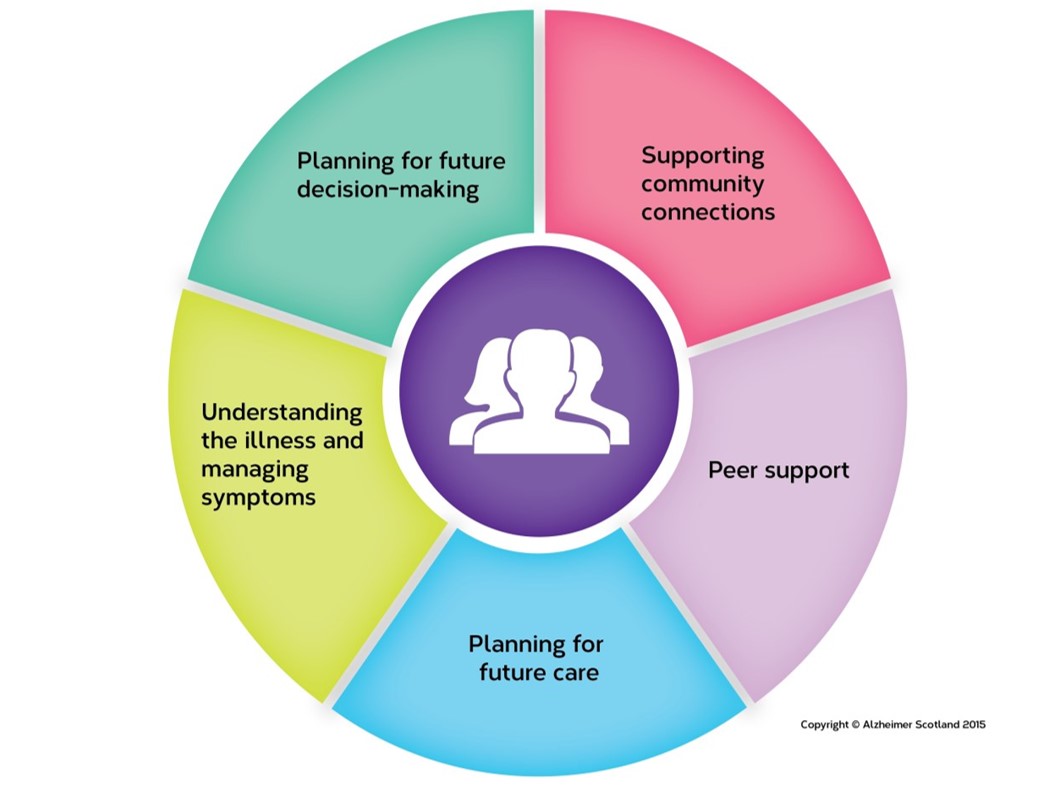

Introducing the Five Pillar Model of Post Diagnostic Support

The Five Pillar Model was developed independently by Alzheimer Scotland in 2011 and serves as the foundation for the PDS system. One of the main reasons for its development was because of strong desires from the outset by people with dementia, particularly within the SDWG established in 2002.

While the benefit of the Link Worker system is that it provides personalized support through individual efforts, there can be significant variations in the content and quality of support depending on the Link Worker. To overcome this issue, Alzheimer Scotland created the 5 Pillar Model to provide guidance. Training courses and educational materials are developed according to this model.

1. Supporting community connections

2. Peer support

3. Planning for future care

4. Understanding the illness and managing symptoms

5. Planning for future decision-making

(Photo: 5 Pillar Model chart from Alzheimer Scotland’s website.)

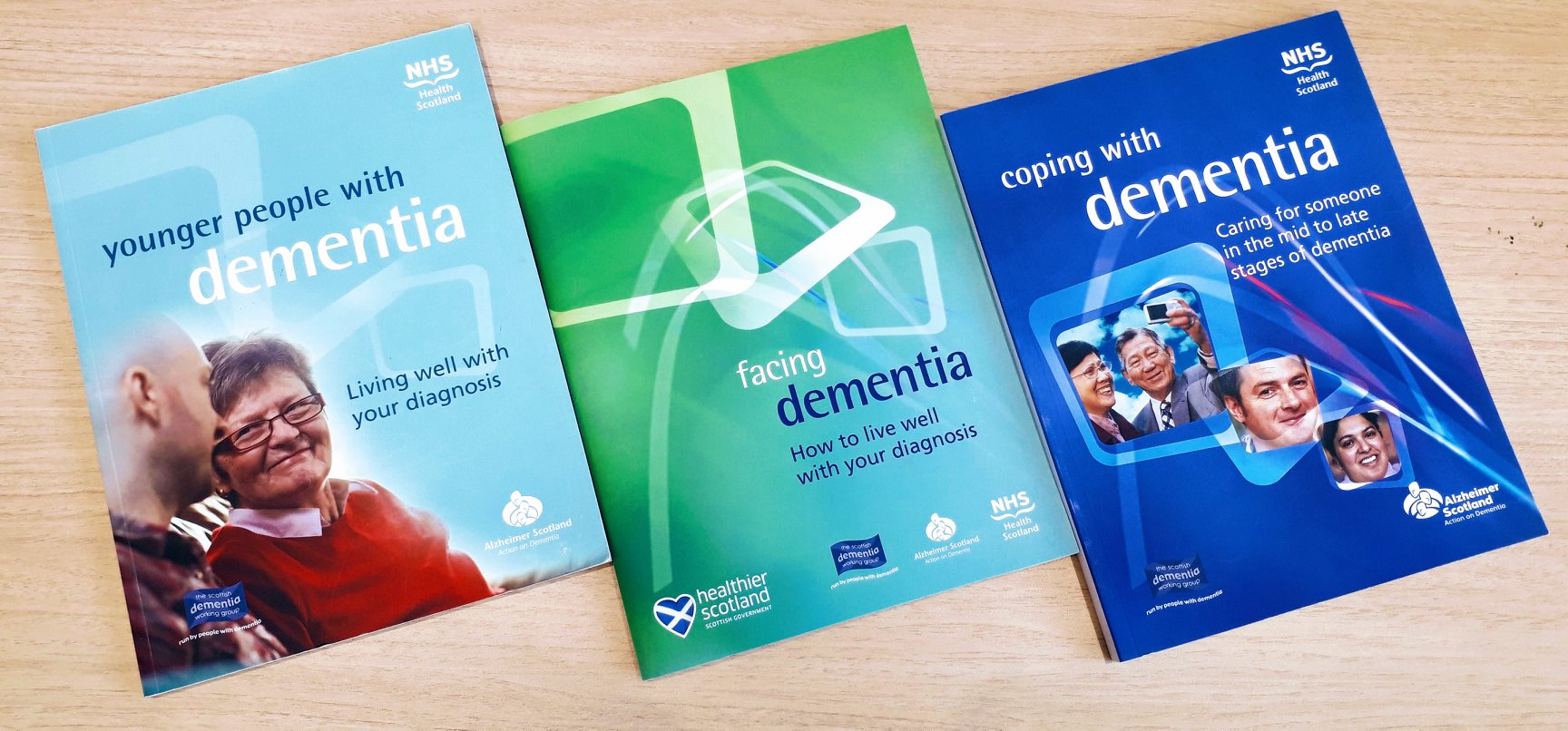

Pictured below are textbooks Link Workers use for promoting understanding among people with dementia and their families. Each pamphlet provides information for various people such as people with early-onset dementia, people in the initial phases of dementia, and people receiving support after their symptoms have advanced.

(Photo: Three textbooks we received during a visit in July 2017.)

Dementia-Friendly Communities Must be Built in Advance

Alzheimer Scotland’s efforts are not limited to only providing PDS. They have prepared a support menu which outlines the series of events in dementia support according to the progression of dementia symptoms.

(Photo: Patient Journey from Alzheimer Scotland’s website.)

For example, during the period before dementia diagnosis, activities are undertaken to promote the creation of dementia-friendly communities in each region. Staff members called Dementia Advisors work to identify local resources available through volunteer organizations and dementia cafés as well as through the government, businesses, and schools. They then work to build community networks between those parties. , Dementia Advisors respond to requests for consultations related to dementia from community members regardless of the degree to which symptoms have progressed for the person in question. There are even cases when these consultations lead to people receiving diagnoses from medical specialists. Alzheimer Scotland also operates a 24-hour Helpline to provide around-the-clock consultations to people with dementia or their family members.

Alzheimer Scotland has established Resource Centres in every region to serve as bases of operation for these community-building efforts. While this is a very general explanation, it might be best to think of them as community centers for comprehensive support that specialize in dementia. Some of the Resource Centres hold dementia cafés, gatherings for community members, or meetings for local healthcare and welfare professionals. Also, Link Workers’ activities are based at every Resource Centre. These Centres serve as local hubs for providing dementia support in each region.

(Photo: A Resource Centre. Taken during a visit in November 2018.)

In Conclusion

This column and our last column focused on Blank Periods and this column introduced Scotland’s PDS system as one potential solution for overcoming them. The PDS system emphasizes the right to self-determination. It is concerned not only with how to provide support to people with dementia or their families, but also with removing hurdles to enable people to exercise self-determination in their everyday lives.

The Blank Periods overlap with especially important periods during which people with dementia must plan their future everyday lives. I believe support during the Blank Periods should be of the type that enables people to make decisions for themselves rather than being direct support. I have heard that the right of self-determination is, overall, more widely-recognized in Europe than Japan, and I believe that Scotland’s unique history has greatly influenced the creation of the PDS system. The people of Scotland may subconsciously place self-determination as a core value, as if to say “We will decide our own affairs by ourselves.”

In Japan, discussions on topics related to people with dementia such as employment and social participation are being held more frequently since the Framework for Promoting Dementia Care was presented. However, whether or not someone with dementia works or is socially active is not important. What is important is that they decide for themselves how they want to live based on their own circumstances. Deciding where to live or work is to exercise fundamental human rights pertaining to psychological freedom, physical freedom, and economic freedom. To ensure that the fundamental human rights of people with dementia receive the same respect as the rights of everyone else, we must consider policies that emphasize the right to self-determination.

I would be especially pleased if this, our first column to be published in 2020, provides you with an opportunity to reflect on efforts in dementia support.

[Reference materials]

Kurita, Shunichiro. 2017. “Suggestions for Japan from Link Workers.” Kenkohoken, No71-11, 26-31.

About the author

Shunichiro Kurita (HGPI Senior Associate; Steering Committee Member, Designing for Dementia Hub)

Top Research & Recommendations Posts

- [Policy Recommendations] Reshaping Japan’s Immunization Policy for Life Course Coverage and Vaccine Equity: Challenges and Prospects for an Era of Prevention and Health Promotion (April 25, 2025)

- [Research Report] Perceptions, Knowledge, Actions and Perspectives of Healthcare Organizations in Japan in Relation to Climate Change and Health: A Cross-Sectional Study (November 13, 2025)

- [Research Report] The 2025 Public Opinion Survey on Healthcare in Japan (March 17, 2025)

- [Research Report] The 2026 Public Opinion Survey on Healthcare in Japan (February 13, 2026)

- [Research Report] 2019 Survey on Healthcare in Japan

- [Research Report] Building a Mental Health Program for Children and Measuring its Effectiveness (June 16, 2022)

- [Research Report] The Public Opinion Survey on Child-Rearing in Modern Japan (Final Report) (March 4, 2022)

- [Policy Recommendations] Developing a National Health and Climate Strategy for Japan (June 26, 2024)

- [Research Report] The 2023 Public Opinion Survey on Satisfaction in Healthcare in Japan and Healthcare Applications of Generative AI (January 11, 2024)

- [Policy Recommendations] Mental Health Project: Recommendations on Three Issues in the Area of Mental Health (July 4, 2025)

![[Registration Open] Online Seminar “Implementing Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) Measures into Society: Towards a Data-Driven Health System” (April 21, 2026)](https://hgpi.org/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/HGPI_20260421_CKDonlineseminar-.png)