[HGPI Policy Column] No. 6 – From the Dementia Policy Team

date : 1/15/2020

Tags: Dementia, HGPI Policy Column

![[HGPI Policy Column] No. 6 – From the Dementia Policy Team](https://hgpi.org/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/column-6.jpg)

Looking back on our previous column

Our previous column focused on sharing the perspectives of local governments on the Basic Law for Dementia which was recently submitted to the Diet. We mentioned that as regional initiatives grow more important in the future, members of the public like us must be aware of the ideal methods for formulating plans at local governments and keep a close eye on the processes used to formulate those plans.

Of the many issues in dementia policy, our next topic of focus is blank periods. In this column and the next, we will examine what happens during blank periods that occur after diagnosis in Japan. We will also share examples from abroad that may hold the potential to overcome these blank periods.

What are the blank periods?

Although recognition towards the necessity of early dementia diagnosis is growing, the fact that support is needed during the period immediately after the diagnosis is not widely-recognized. Blank periods are periods during which adequate support is not provided. Social isolation increases during blank periods, lowering the quality of life (QOL) for people with dementia.

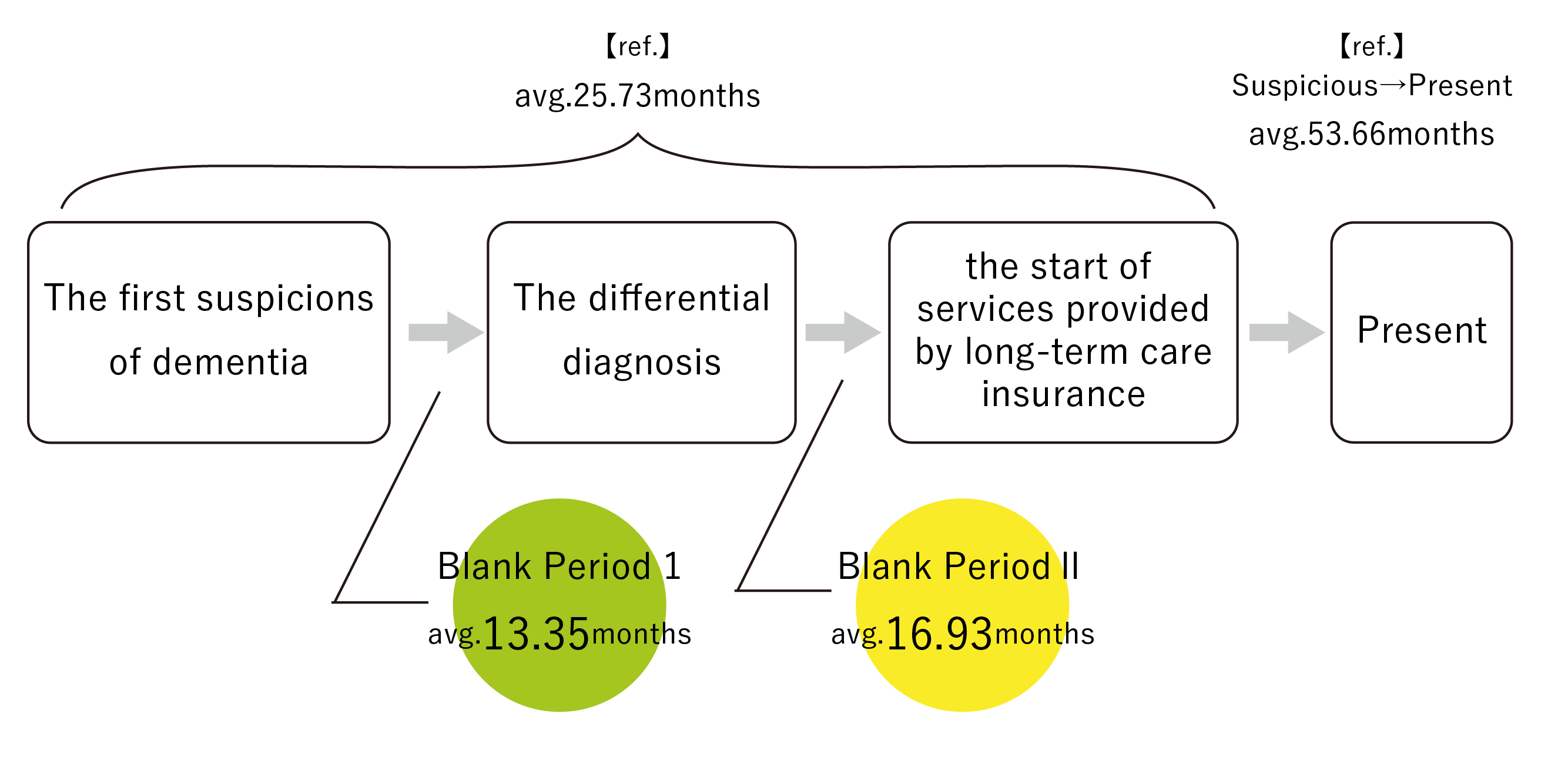

Of the studies conducted on blank periods, one prominent study was “A Study About the Family Support for Person with Dementia” conducted by the Sendai Dementia Care Research and Training Center in FY2017. It asked dementia caregivers including family members about the current circumstances of their blank period, identified the following characteristics, and sorted blank periods into one of two types.

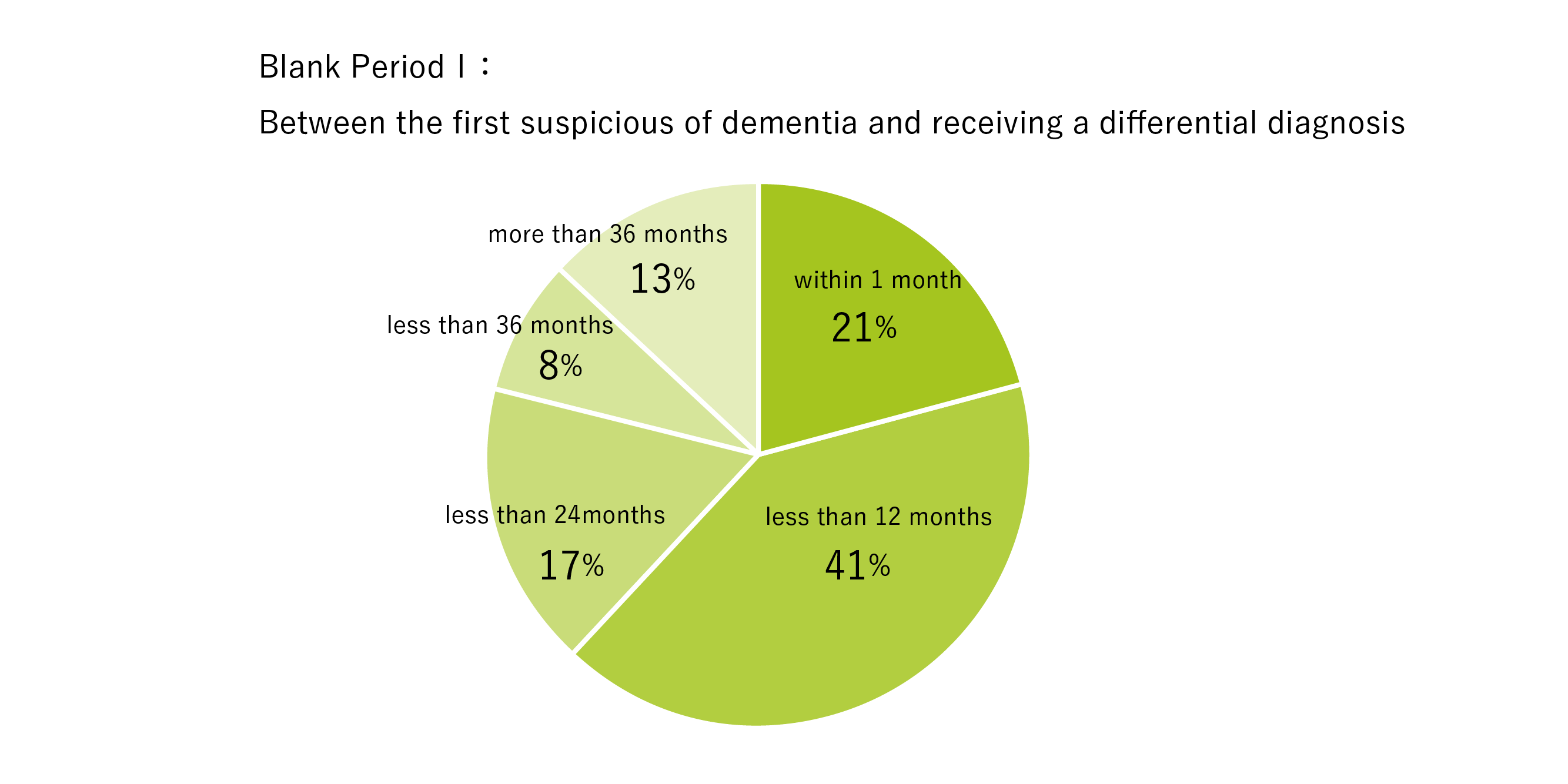

Blank Period 1: Between the first suspicions of dementia and receiving a differential diagnosis

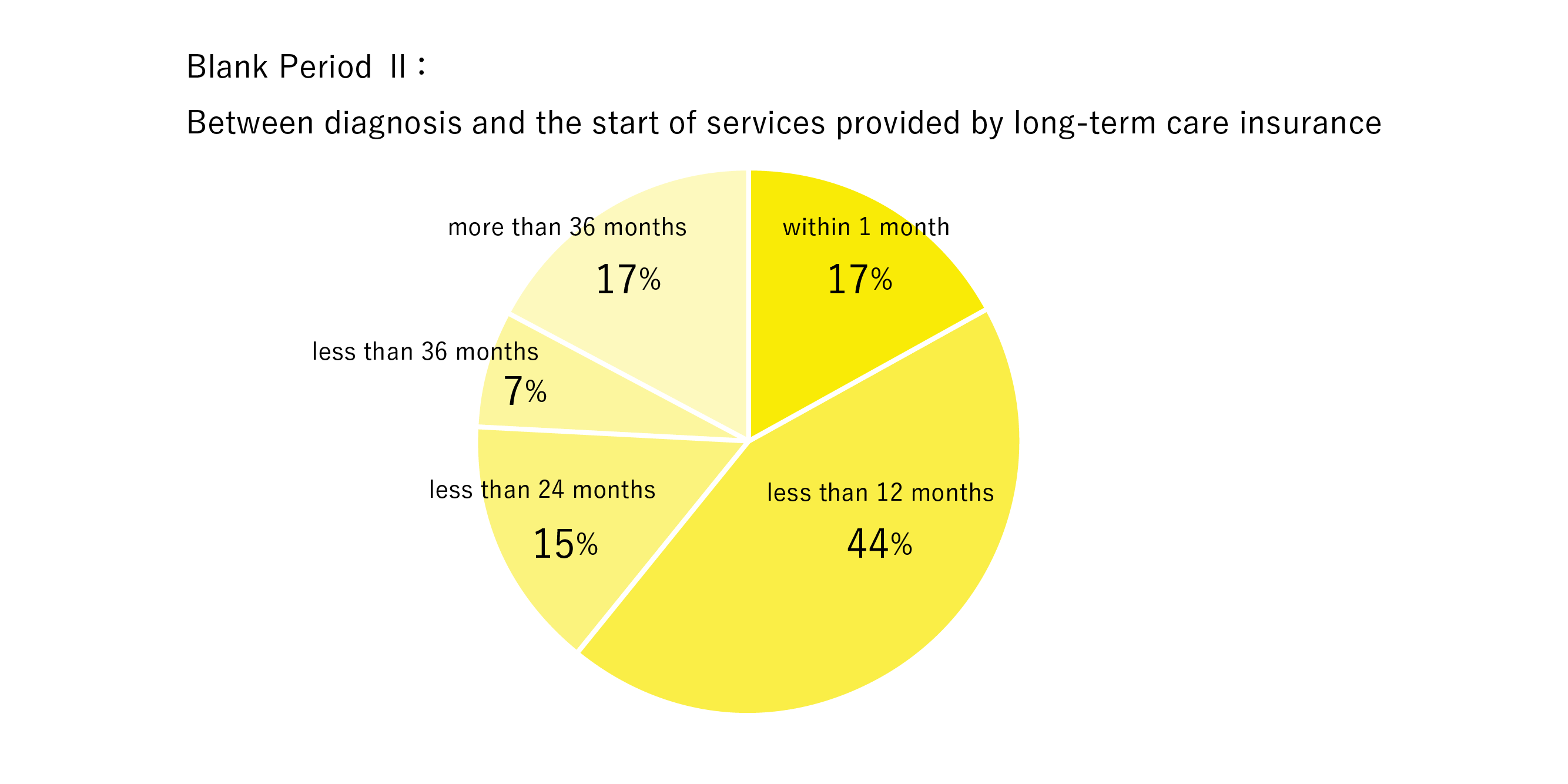

Blank Period 2: Between diagnosis and the start of services provided by long-term care insurance

Reference: Sendai Dementia Care Research and Training Center, 2018. “A Study About the Family Support for Person with Dementia” (Retrieved January 8, 2019)

During Blank Period 1, 21% of respondents received a diagnosis within one month while 40.9% received a diagnosis after one month but within twelve months. In other words, 61% of respondents received a diagnosis within one year.

Reference: Sendai Dementia Care Research and Training Center, 2018. “A Study About the Family Support for Person with Dementia” (Retrieved January 8, 2019)

During Blank Period 2, 61.2% of respondents were able to start using long-term care insurance services within one year. Meanwhile, 17.1% of respondents had to wait three years or more to start using long-term care insurance services.

Reference: Sendai Dementia Care Research and Training Center, 2018. “A Study About the Family Support for Person with Dementia” (Retrieved January 8, 2019)

The report also examined the relationship between the subjective feelings of burden among family members and other caregivers and the length of the blank period. Although there was no significant relationship between subjective feelings of burden and period length during Blank Period 1, longer period length during Blank Period 2 led to more intense feelings of psychological, physical, and economic burden.

Current methods of providing support during blank periods in Japan

The Initial-phase Intensive Support Team System for Dementia

As demonstrated by the aforementioned study, overcoming blank periods is a high-priority issue. Since people with dementia have limited ability to use services such as those provided by long-term care insurance during blank periods, new forms of institutional support are sorely needed. These blank periods overlap with periods when it is crucial for the person diagnosed with dementia and their family members to prepare for life with dementia. Before symptoms progress, people with dementia and their family members require support to understand dementia, to accept dementia, and to think about how they want to live their everyday lives.

I would like to give a simple description of current efforts in Japan. In the present system, the initiative closest to providing direct blank period support is the Initial-phase Intensive Support Team System for Dementia. It was started as part of the 2014 revision of the long-term care insurance system, which aimed to strengthen existing integrated support activities under a law that defined such activities as, “Support provided to prevent the worsening of dementia symptoms through early detection by people with specialized knowledge in health insurance or welfare, or comprehensive support activities for insured individuals who are suspected to have dementia.” Initial-phase Intensive Support Teams have been established in almost every municipality in Japan since FY2018.

Initial-phase Intensive Support Teams are defined by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) as “Teams of various specialists who respond to inquiries from family members and other such notifications by visiting people who are suspected to have dementia, people with dementia, or their family members (known as “outreach activities”). These teams conduct assessments and provide initial integrated and intensive support to the families during the period immediately after diagnosis (defined as approximately six months) as well as support for independent living” (MHLW, 2014, p11).

The following people are considered eligible for support through this program:

“People age 40 and over living in private homes and who are suspected to have dementia or have dementia and for whom one of the following two conditions applies.

(1) People who are not receiving medical or long-term care services or have suspended their reception of such services, and for whom one of the following conditions applies:

A. They have not received a clinical diagnosis of dementia

B. They are not undergoing continuous medical care

C. They have not been introduced to appropriate long-term care insurance services

D. They have been diagnosed but have suspended long-term care insurance services

(2) People who are receiving medical or long-term care insurance services but display behavioral or psychological symptoms of dementia and are struggling to cope with them.”

People in the initial stages of dementia are not the only ones eligible for support through this service. People making their first contact with care services are also eligible. That is why the conditions include a clause stating, “People whose dementia has progressed past the initial stages but have not yet been in contact with medical or long-term care” (Nobi, 2016, P428). Also, “intensive support” in the context of this system means “Integrated and intensive support including assessment and family support provided for approximately six months. After support to promote independent living has been provided, efforts will be made to connect the person with dementia to future healthcare services and care teams” (Tsurumi, 2015, P851).

Reviewing the details of this system, one might say that the central roles of Initial-phase Intensive Support Teams are to reduce the number of people who slip through the cracks of medical and long-term care insurance services and to connect as many people as possible to such services. These efforts correspond to Blank Period 1 in the aforementioned study.

Building Peer Support Systems

Establishing peer support systems for people with dementia in every region and municipality is one of the goals of the Framework for Promoting Dementia Care, a law presented by the Japanese government in June 2019 that we have discussed multiple times in past columns.

During periods such as the one immediately following diagnosis, people may not be able to accept dementia and may feel great unease towards the future. When someone with dementia has accepted their diagnosis, has overcome their unease, and can share their desire to live a positive and active life, they can act as a peer supporter who provides early support for the psychological and lifestyle aspects of living with dementia to others. We will support efforts of people with dementia to engage in peer support activities. Also, in order to provide support immediately after diagnosis, we will publicize educational materials such as the “Guide for Living a Better Life with Dementia from a Firsthand Perspective” which includes information and advice on how people with dementia can live their everyday lives, or the DVD entitled “Conversations with People with Dementia,” which contains messages from people with dementia and stories of their experiences (Framework for Promoting Dementia Care, P6).

Because peer support provides people with dementia the opportunity to receive help with their questions and concerns from other people with dementia, systems for peer support have a major role to play. However, within the Framework, peer support is covered under the heading “Promoting public awareness and supporting efforts made by people with dementia to disseminate their stories and opinions among the public.” This gives the impression that peer support activities will first emphasize the promotion of public awareness and then expand gradually rather than be used as a significant source of support right away.

In Conclusion

I have listened to the stories of a great number of people with dementia and their family members and have experienced life as a family caregiver to someone with dementia myself. These experiences have taught me that people diagnosed with dementia experience unease towards a wide variety of things, not only towards treatment and care. However, measures for providing post-diagnostic support are progressing, be it specialized medical and long-term care support from professionals, or psychological support provided by people with dementia sharing their own experiences.

On the other hand, just because someone has been diagnosed with dementia does not mean that they can suspend their everyday lives and wait for support. They must think about the overall circumstances of their everyday lives. This includes factors within the household like the household budget and relationships with family members. If they are still of working age, they must also think about their job. The connections they have built with friends and their communities must also be considered. On these points, the support systems in Japan still have a long way to go. I believe many people who are diagnosed with dementia are confused about who to consult and when. Support is especially lacking during Blank Period 2, which was demonstrated to cause more intense feelings of mental, physical, and economic burden the longer it lasts. Focused support for this period is needed.

In our next column, we will introduce post-diagnostic support systems currently being used in Scotland, a world leader in dementia policy. While some elements of their system have been adopted in Japan, not much has been shared about the system overall. Over the past several years, HGPI has investigated and researched dementia policy in Scotland, so I would like to share some of our findings with you. Please look forward to it.

[Reference materials]

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. “Enhancing Regional Support Initiatives and Reviewing Preventive Care” (2014a).

Sendai Dementia Care Research and Training Center, 2018. “A Study About the Family Support for Person with Dementia” https://www.dcnet.gr.jp/support/research/center/detail_322.php (Retrieved January 8, 2019)

Ministerial Council on the Promotion of Policies for Dementia Care, 2019. “Framework for Promoting Dementia Care.”

Nobu, Ikuko. 2016. “Current Situation of Initial-Phase Intensive Support Team.” The Japanese Society for Dementia Care Journal of Japanese Society for Dementia Care, Volume 15, No 2.

Washimi, Yukihiko. 2015. “Dementia Support Teams and Initial-Phase Intensive Support Teams.” Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, Volume 253, No 9.

About the author

Shunichiro Kurita (HGPI Senior Associate; Steering Committee Member, Designing for Dementia Hub)

Top Research & Recommendations Posts

- [Policy Recommendations] The Path to a Sustainable Healthcare System: Three Key Objectives for Public Deliberation (January 22, 2026)

- [Research Report] Perceptions, Knowledge, Actions and Perspectives of Healthcare Organizations in Japan in Relation to Climate Change and Health: A Cross-Sectional Study (November 13, 2025)

- [Research Report] The 2025 Public Opinion Survey on Healthcare in Japan (March 17, 2025)

- [Policy Recommendations] Reshaping Japan’s Immunization Policy for Life Course Coverage and Vaccine Equity: Challenges and Prospects for an Era of Prevention and Health Promotion (April 25, 2025)

- [Research Report] The 2023 Public Opinion Survey on Satisfaction in Healthcare in Japan and Healthcare Applications of Generative AI (January 11, 2024)

- [Research Report] AMR Policy Update #4: Cancer Care and AMR (Part 1)

- [Policy Recommendations] Developing a National Health and Climate Strategy for Japan (June 26, 2024)

- [Public Comment Submission] “Assessment Report on Climate Change Impacts in Japan (Draft Overview)” (December 24, 2025)

- [Research Report] Survey of Japanese Physicians Regarding Climate Change and Health (December 3, 2023)

- [Research Report] The Public Opinion Survey on Child-Rearing in Modern Japan (Final Report) (March 4, 2022)

Featured Posts

-

2026-01-09

[Registration Open] (Hybrid Format) Dementia Project FY2025 Initiative Concluding Symposium “The Future of Dementia Policy Surrounding Families and Others Who Care for People with Dementia” (March 9, 2026)

![[Registration Open] (Hybrid Format) Dementia Project FY2025 Initiative Concluding Symposium “The Future of Dementia Policy Surrounding Families and Others Who Care for People with Dementia” (March 9, 2026)](https://hgpi.org/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/dementia-20260309-top.png)

-

2026-02-05

[Registration Open] (Webinar) The 141st HGPI Seminar “Current Status and Future Prospects of Korea’s Obesity Policy: Voices of People with Lived Experience in Policy Promotion” (March 3, 2026)

![[Registration Open] (Webinar) The 141st HGPI Seminar “Current Status and Future Prospects of Korea’s Obesity Policy: Voices of People with Lived Experience in Policy Promotion” (March 3, 2026)](https://hgpi.org/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/hs141-top-1.png)

-

2026-02-06

[Research Report] AMR Policy Update #5: Cancer Care and AMR (Part 2)

![[Research Report] AMR Policy Update #5: Cancer Care and AMR (Part 2)](https://hgpi.org/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/HGPI_20260204_AMR-Policy-Update-5.png)