[HGPI Policy Column] (No.66) — From the Planetary Health Project “Part 16: The Global Plastics Treaty: Discourse on Human Health in International Environmental Law”

date : 12/9/2025

![[HGPI Policy Column] (No.66) — From the Planetary Health Project “Part 16: The Global Plastics Treaty: Discourse on Human Health in International Environmental Law”](https://hgpi.org/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/HGPI_20251208_PlasticsTreaty.png)

<POINTS>

- Plastic pollution is no longer just an environmental issue but a significant global health security concern. Hazardous chemicals from plastics have been linked to various health problems, and the discovery of microplastics in human bodies continues to pose unknown risks.

- Since 2022, the path to a Global Plastics Treaty has been fraught with challenges, marked by fundamental disagreements between nations advocating for ambitious, health-protective regulations (including production caps) and those prioritizing waste management and economic development.

- The conclusion of the INC-5.2 in Geneva, Switzerland could not reach a final agreement on the treaty due to significant disagreements on core issues such as production, specific plastic products, and funding mechanisms, necessitating further rounds of negotiations to be held at a later date.

- Domestically, Japan’s initiatives focus on a comprehensive lifecycle approach to plastics, emphasizing resource circulation. In addition, Japan has been active in monitoring and data collection globally (particularly in ocean microplastics), presenting an opportunity for Japan to lead with innovative solutions grounded on evidence.

Introduction

Since its commercial introduction in the mid-20th century, plastic has transformed nearly every aspect of modern life, from medicine and engineering to everyday consumer goods. However, this transformation has come at a cost: the escalating plastic pollution now poses significant threats to both environmental and public health, making it one of the most pressing challenges in contemporary environmental policy. The conclusion of the second part of the fifth session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC-5.2) in Geneva, Switzerland, underscored both the urgency and complexity of addressing this global challenge. Despite intensive negotiations, securing a comprehensive Global Plastics Treaty remains elusive, representing a critical test for international environmental diplomacy and multilateral cooperation. This policy column analyzes the complex international negotiating process, examines Japan’s evolving position and contributions to these discussions, and explores how global developments intersect with domestic plastic policy initiatives.

Plastic Pollution as a Health Security Issue

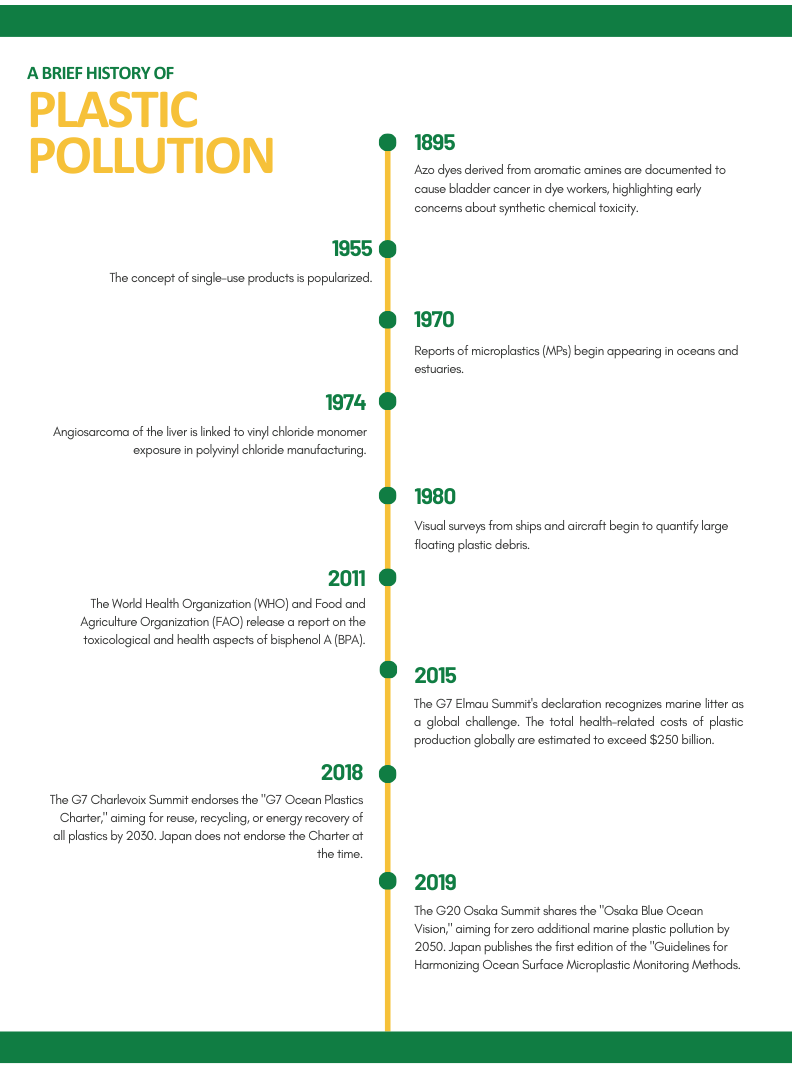

Figure 1: A brief history of plastic pollution

The recognition of plastic pollution as a global health security issue reflects an acknowledgement of the deep connections between ecological damage and human wellbeing. Current projections indicate that without decisive interventions, plastic waste entering water systems could surge from 23 million to 37 million tons annually by 2040, fundamentally changing the relationship between humans and their environment. Recent findings published by the Minderoo-Monaco Commission in 2023 highlighted that plastics harm both human and planetary health, from heightened risk of childhood cancer brought about by early exposure to plastics, to the discovery of microplastic and nanoplastic particles (MNPs) in marine species, including species consumed by humans. This trajectory raises concerns regarding large-scale introductions of new chemical compounds with poorly understood long term-effects on human health.

Scientific evidence supporting this concern has grown in recent years. The dangers of plastics to human health were first recognized as early as the 1970s, through four cases of hepatic angiosarcoma among polyvinyl chloride (PVC) polymerization workers in Kentucky, USA. Since then, research has identified over 16,000 chemicals used in plastic production processes, with at least 4,200 classified as “highly hazardous” to human health and environmental systems, yet only 6% are currently regulated by international treaties. Food contact materials such as tableware, food containers, drinking water bottles, sachets, and food processing equipment can all release chemicals, which then enter the human body through ingestion, inhalation, and dermal absorption.

The health implications are serious, with peer-reviewed studies establishing clear links between plastic-related chemicals and various health problems, including cancers, genetic mutations, reproductive system damage, neurological dysfunction, and weakened immune systems. The discovery of microplastics in human blood and breastmilk underscores the urgency of developing comprehensive policies. From a health economics perspective, the costs of regulatory inaction on this chemical and plastic pollution crisis are projected to reach 10% of global GDP, with health-related damages alone estimated at hundreds of billions of dollars annually.

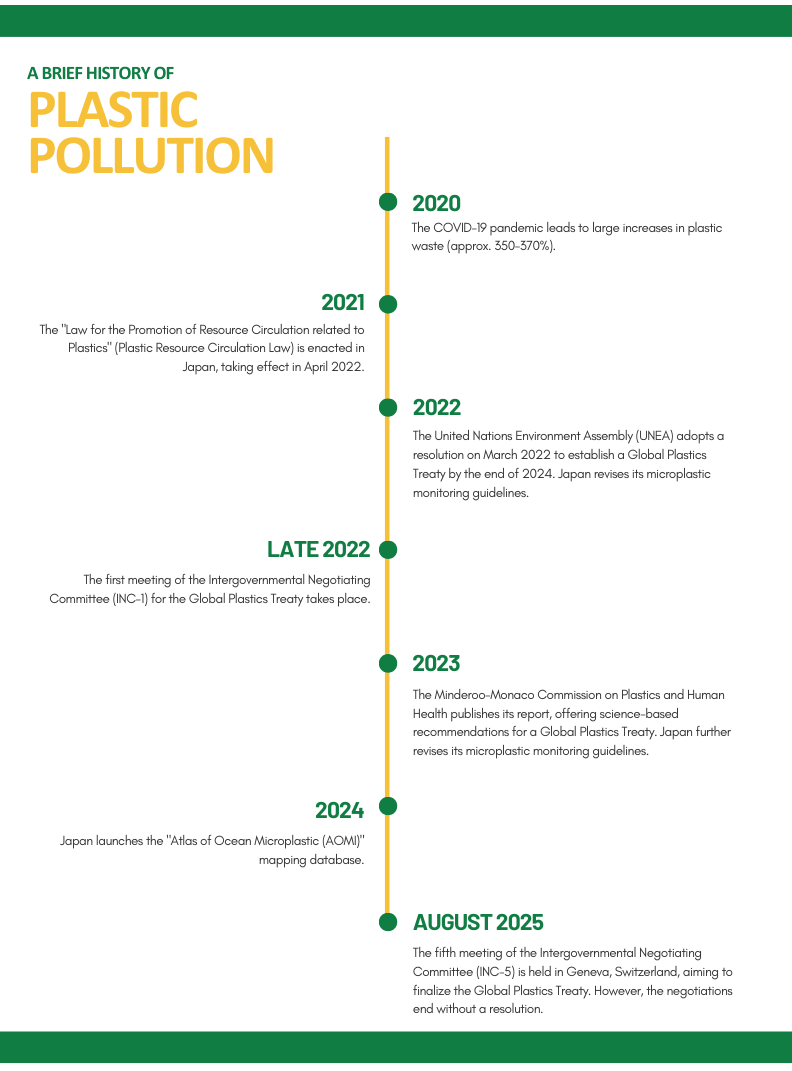

In response to this, the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA-5.2) adopted a historic resolution in March 2022 to develop an international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution by the end of 2024, taking a comprehensive approach to the entire lifecycle of plastics. However, the path to a robust treaty has not been easy. Negotiations at INC-1 (Uruguay), INC-2 (Paris), INC-3 (Nairobi), INC-4 (Ottawa), and INC-5.1 (Busan) have largely been divisive.

Figure 2: Overview of International Negotiating Committee (INC) negotiations

International Environmental Law Negotiations and Health Integration

At the current pace of plastic production, recycling alone fails to eradicate the problem, as only less than 10% of all plastic waste is currently recycled worldwide, necessitating a full life-cycle approach to the plastic crisis. International efforts to regulate plastic have been shaped by competing approaches between market-focused and health-first approaches. The negotiating process at the Global Plastics Treaty discussions has also revealed fundamental disagreements about the scope and intensity of international regulation.

Over 100 nations have advocated for plastic production caps and strict chemical regulation based on precautionary principles. Their emphasis on a full-lifecycle approach reflects growing recognition that effective health protection requires intervention at all stages of plastic production, distribution, use, and disposal. In contrast, major petrochemical-producing states, including Saudi Arabia, the United States, Russia, and China, have favored regulatory frameworks that prioritize waste management over production restrictions, viewing plastics as essential to economic development. Notably, some negotiations have seen proposals to remove treaty sections addressing supply chains or health considerations entirely, indicating the depth of disagreement over how broad regulations should be.

Financial mechanisms represent another critical part of the negotiations, with developing countries emphasizing that treaty implementation requires “adequate, accessible, new, and additional financial resources.” Some countries have proposed compensation mechanisms for pollution-related damages, reflecting broader debates about environmental justice and shared responsibilities. Financing schemes have been suggested, such as the Polymer Premium, which could help bridge the fiscal gap especially for developing countries. These discussions are closely linked to health considerations, as developing countries often experience disproportionate health burdens from plastic pollution while having limited ability to regulate it.

Despite high hopes, the fifth session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee’s resumed meeting (INC 5.2) held from August 5 to 15, 2025, concluded without reaching a substantive agreement on the Global Plastics Treaty. Despite intensive negotiations across four working groups, significant differences of opinion remained on key articles, including those concerning production, plastic products (Article 4), and finance (Article 10), as well as the Conference of the Parties (Article 18). While progress was made on other articles such as the objective, product design, releases and leakages, waste management, existing plastic pollution, just transition, and implementation and compliance, the negotiations will need to continue in future resumed sessions. Japan actively participated in the meeting, emphasizing the importance of promoting a full lifecycle approach, clear common standards for plastic products, environmentally sound product design, proper waste management (including Extended Producer Responsibility), national action plans, and resource mobilization from all funding sources.

Japan’s Domestic Policy Evolution

Japan’s domestic policy evolution (particularly on ocean plastics) is closely linked to international frameworks. Notably, the G20 Action Plan on Marine Litter, built on the Osaka Blue Ocean Vision which aims to reduce marine plastic litter to zero by 2050, provides a voluntary platform for sharing national policies promoting circular economy initiatives. Complementing this, the G20 Implementation Framework for Actions on Marine Plastic Litter was created to support the practical implementation of the Action Plan. Local initiatives across Japanese prefectures and municipalities also demonstrate Japan’s multi-level approach, ranging from marine litter management systems in Okayama City to symposia on recycling technologies in Tokyo.

The institutional framework supporting Japan’s domestic plastic governance includes amendments to the Law for the Act on Promoting the Treatment of Marine Debris (2018) and the development of a Plastic Resource Circulation Strategy (2019) that emphasizes reduction of single-use plastics, promotion of reuse and recycling, and energy recovery from used plastics. This strategy laid the foundation for later legal actions such as the “Act on Promotion of Resource Circulation for Plastics”, which came to force in April 2022. The act aims to promote the efficient use and conservation of resources and reduce plastic waste throughout the entire lifecycle of plastic products, from design to disposal. The law is based on the fundamental principle of “3R + Renewable,” which stands for Reduce, Reuse, Recycle, and shifting to renewable resources.

Specifically, the law requires businesses to consider resource circulation from the product design stage, including reducing plastic usage, promoting reuse, and incorporating recycled materials. For certain designated categories of single-use plastic products, businesses that provide them are obligated to take measures to reduce and rationalize their use, with specific requirements applying when their efforts are judged insufficient. In addition, companies that generate large volumes of industrial plastic waste must take steps to reduce waste, separate it properly, and promote recycling. Through this framework, the government, local authorities, businesses, and consumers are expected to cooperate in curbing plastic waste by reducing reliance on single-use plastics and enhancing recycling, with the ultimate goal of realizing a circular economy and reducing environmental impacts.

Japan has also been at the forefront of ocean microplastic research. In 2019, Japan published the first edition of its “Guidelines for Harmonizing Ocean Surface Microplastic Monitoring Methods”. These guidelines underwent further revisions in both 2022 and 2023 to incorporate new findings and methodological improvements. Building on this foundation, Japan launched the “Atlas of Ocean Microplastic (AOMI)” mapping database in May 2024, creating a comprehensive resource for tracking microplastic distribution across ocean surfaces.

For a sustainable future, Japan’s plastic policies must continue to evolve. Collaboration among individuals, businesses, and government to shift society from a “disposable” mindset to a “circular” one will be key to preserving the environment.

Economic Benefits of a Global Plastics Treaty

Recent economic analysis commissioned by the Business Coalition for a Global Plastics Treaty, for which WWF Japan serves as the secretariat, provides strong evidence for harmonized regulations regarding plastic pollution. The study shows that implementing international rules for phaseouts/eliminations (Article 3), product design (Article 5), and waste management/EPR (Article 8) would yield significant economic benefits for Japan and other countries adopting similar approaches. For Japan specifically, the analysis indicates the following benefits under global regulations compared to fragmented national approaches by 2040:

- Recycled material production could increase by 90%

- Waste management costs could be reduced by 10% from 2026 to 2040

- International coordination would achieve a 2.25-fold greater reduction in problematic single-use plastics

- Economic activity in the regional plastics value chain (including Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand) is projected to increase by 7%

- Employment in the regional plastics value chain (including Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand) is projected to increase by 5%

These findings suggest that comprehensive international regulation supports both national economic interests and environmental and health protection goals, further indicating that fragmented approaches may impose higher costs on domestic industries while providing fewer health and environmental benefits.

Conclusion

The inconclusive outcome of INC-5.2 in Geneva underscores the persistent challenges facing international environmental diplomacy in addressing complex issues such as plastic pollution. However, Japan’s active participation and comprehensive domestic policy framework position it to demonstrate leadership in pioneering health-protective solutions that align with economic interests. There is compelling evidence that comprehensive international regulation can advance both health protection objectives and national economic interests.

As negotiations continue in future resumed sessions, the trajectory of global plastic governance will significantly influence not only international environmental law but also the broader development of health-centered approaches to 21st-century environmental challenges. The ultimate success of a Global Plastics Treaty will depend on bridging the divide between these approaches, recognizing that the health and economic costs of regulatory inaction far exceed the investments required for comprehensive intervention across the plastic lifecycle.

References

- Business Coalition for a Global Plastics Treaty. (2025). The economic rationale for a Global Plastics Treaty underpinned by mandatory harmonised regulation — A modelling exercise (June 2025). Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Retrieved July 3, 2025, from https://content.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/m/5464570e082d536b/original/Business-Coalition-Economic-Rationale-Modelling-Doc.pdf

- Falk, H. (1987). Vinyl chloride-induced hepatic angiosarcoma. Princess Takamatsu Symposium, 18, 39–46. Retrieved July 3, 2025, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3506545/

- G20 Marine Plastic Litter. (2024). Towards Osaka Blue Ocean Vision: G20 implementation framework for actions on marine plastic litter. https://g20mpl.org/

- Global Plastic Laws. (n.d.). UN plastics treaty. Retrieved July 3, 2025, from https://www.globalplasticlaws.org/un-global-plastics-treaty

- Government of Japan. (2024, November 25). Japan national statement under agenda item 4, INC-5: The fifth session of Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee to develop an international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment [PDF]. United Nations Environment Programme. Retrieved July 3, 2025, from https://resolutions.unep.org/incres/uploads/japan_national_statement_under_agenda_4_inc5.pdf

- Health Policy Watch. (2025, April 17). The health crisis that could make or break the UN plastics treaty. Retrieved July 3, 2025, from https://healthpolicy-watch.news/the-health-crisis-that-could-make-or-break-the-un-plastics-treaty/

- ICLEI Japan. (n.d.). Call for participation in the Global Plastic Treaty to reduce plastic use. Retrieved July 3, 2025, from https://japan.iclei.org/en/news/call-for-participation-in-the-global-plastic-treaty/

- Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee. (2025, February 10). Draft report of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee to develop an international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment, on the work of the first part of its fifth session (UNEP/PP/INC.5/8) [PDF]. United Nations Environment Programme. Retrieved July 3, 2025, from https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/47162/INC_5_1_Report.pdf

- Kyodo News. (2024, June 3). Over 70 nations to call for international plastic pollution reduction targets. Kyodo News. Retrieved July 3, 2025, from https://english.kyodonews.net/articles/-/54762?phrase=Toshiba+&words=

- Landrigan, P. J., Dunlop, S., Treskova, M., Raps, H., Symeonides, C., Muncke, J., et al. (2025). The Lancet Countdown on health and plastics. The Lancet. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(25)01447-3

- Landrigan, P. J., Raps, H., Martins, D., et al. (2023). The Minderoo-Monaco Commission on Plastics and Human Health. Annals of Global Health, 89(1), Article e1. https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.4056

- Michida, Y., et al. (2019). Guidelines for harmonizing ocean surface microplastic monitoring methods. Ministry of the Environment Japan.

- Minderoo Foundation. (2024). The polymer premium: A fee on plastic pollution. Retrieved July 3, 2025, from https://cdn.minderoo.org/content/uploads/2024/04/21232940/The-Polymer-Premium-a-Fee-on-Plastic-Pollution.pdf

- Ministry of the Environment. (2009). Act on promoting proper treatment of coastal drift debris. e-Gov Law Search. Retrieved July 3, 2025, from https://laws.e-gov.go.jp/law/421AC1000000082

- Ministry of the Environment. (2019). Plastic resource circulation strategy. Retrieved July 3, 2025, from https://plastic-circulation.env.go.jp/about/senryaku

- Ministry of the Environment. (2024). Summary of outcomes of the fifth session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee for the development of an international legally binding instrument (treaty) on plastic pollution. Retrieved July 3, 2025, from https://www.env.go.jp/press/press_04058.html

- Ministry of the Environment, Government of Japan. (2025, August 5). Summary of the fifth resumed session of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee for a legally binding international agreement on plastic pollution. Retrieved September 10, 2025, from https://www.env.go.jp/press/press_00461.html

- Ministry of the Environment, Japan. (2024, May 8). Release of the marine plastic litter mapping database “Atlas of Ocean Microplastics (AOMI).” Retrieved July 3, 2025, from https://www.env.go.jp/en/press/press_02788.html

- Ministry of the Environment, Japan. (n.d.). Atlas of Ocean Microplastics (AOMI). Retrieved August 22, 2025, from https://aomi.env.go.jp/

- Okayama City. (2023, June 19). Marine Litter Gatekeeper. Retrieved July 9, 2025, from https://www.city.okayama.jp/harmonia/0000049028.html

- Rever Co., Ltd. (2023, February 9). Understanding the Plastic Resource Circulation Promotion Act in 10 minutes: The act and the wide-area certification system. Ecoo Online. Retrieved July 3, 2025, from https://www.re-ver.co.jp/ecoo-online/waste-disposal-low/20220208.html

- The Japan Times. (2024, November 29). Showdown looms on plastic treaty days before deadline. The Japan Times. Retrieved July 3, 2025, from https://www.japantimes.co.jp/environment/2024/11/29/plastics-treaty-showdown/

- Tokyo Metropolitan Government. (2023, April 4). Online symposium: The future of plastic recycling – Advanced technologies for closed-loop recycling [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved July 3, 2025, from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U_rLm4IkWlg

- United Nations Environment Programme. (2025). Chair’s revised text proposal – 15 August 2025 as at 00:48. Retrieved September 10, 2025, from https://resolutions.unep.org/incres/uploads/chairs_revised_draft_text_proposal_-_15.08.25_at_00.482.pdf

- WWF Japan. (2025, June 27). New analysis released ahead of final negotiations on the international plastics treaty: Legally binding, harmonized rules benefit economic activities—Plastic-related economic activities projected to increase by 31% globally. Retrieved July 3, 2025, from https://www.wwf.or.jp/press/5993.html

- Wheeler, J. B., & Solomon, H. (1974). Angiosarcoma of liver in the manufacture of polyvinyl chloride. Journal of Occupational Medicine, 16(3), 150–151. Retrieved July 3, 2025, from https://doi.org/10.1097/00043764-197403000-00005

- Yamamoto MRC. (2025). What is the Plastic Resource Circulation Promotion Act? Overview and explanation of the 12 targeted items. Retrieved July 3, 2025, from https://www.yamamoto-mrc.co.jp/column/industrial/1526/

- Zimmermann, L., Scheringer, M., Geueke, B., et al. (2022). Implementing the EU chemicals strategy for sustainability: The case of food contact chemicals of concern. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 437, 129167. Retrieved July 3, 2025, from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.129167

Authors

Gail Co (Program Specialist, Health and Global Policy Institute)

Joji Sugawara (Vice President, Health and Global Policy Institute)

Top Research & Recommendations Posts

- [Research Report] Perceptions, Knowledge, Actions and Perspectives of Healthcare Organizations in Japan in Relation to Climate Change and Health: A Cross-Sectional Study (November 13, 2025)

- [Policy Recommendations] Reshaping Japan’s Immunization Policy for Life Course Coverage and Vaccine Equity: Challenges and Prospects for an Era of Prevention and Health Promotion (April 25, 2025)

- [Research Report] The 2025 Public Opinion Survey on Healthcare in Japan (March 17, 2025)

- [Research Report] The 2026 Public Opinion Survey on Healthcare in Japan (February 13, 2026)

- [Research Report] 2019 Survey on Healthcare in Japan

- [Research Report] Building a Mental Health Program for Children and Measuring its Effectiveness (June 16, 2022)

- [Policy Recommendations] Developing a National Health and Climate Strategy for Japan (June 26, 2024)

- [Research Report] The Public Opinion Survey on Child-Rearing in Modern Japan (Final Report) (March 4, 2022)

- [Policy Recommendations] Mental Health Project: Recommendations on Three Issues in the Area of Mental Health (July 4, 2025)

- [Research Report] The 2023 Public Opinion Survey on Satisfaction in Healthcare in Japan and Healthcare Applications of Generative AI (January 11, 2024)

Featured Posts

-

2026-01-09

[Registration Open] (Hybrid Format) Dementia Project FY2025 Initiative Concluding Symposium “The Future of Dementia Policy Surrounding Families and Others Who Care for People with Dementia” (March 9, 2026)

![[Registration Open] (Hybrid Format) Dementia Project FY2025 Initiative Concluding Symposium “The Future of Dementia Policy Surrounding Families and Others Who Care for People with Dementia” (March 9, 2026)](https://hgpi.org/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/dementia-20260309-top.png)

-

2026-02-27

[Registration Open] (Webinar) The 142nd HGPI Seminar “World Kidney Day 2026” Theme in Focus: The Current State of Green Nephrology and Green Dialysis—Balancing Kidney Health and Planetary Health (March 10, 2026)

![[Registration Open] (Webinar) The 142nd HGPI Seminar “World Kidney Day 2026” Theme in Focus: The Current State of Green Nephrology and Green Dialysis—Balancing Kidney Health and Planetary Health (March 10, 2026)](https://hgpi.org/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/The142nd_HGPI_Seminar.jpg)

-

2026-03-03

[Registration Open] Online Seminar “Implementing Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) Measures into Society: Towards a Data-Driven Health System” (April 21, 2026)

![[Registration Open] Online Seminar “Implementing Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) Measures into Society: Towards a Data-Driven Health System” (April 21, 2026)](https://hgpi.org/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/HGPI_20260421_CKDonlineseminar-.png)