[HGPI Policy Column] (No. 65) From the Dementia Project “The Future of Dementia Research Co-created with affected parties, Vol.3: A Stage Theory of Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) in Medical Research on Dementia and Commentary and Recommendations on PPI Evaluation”

date : 10/29/2025

Tags: Dementia, HGPI Policy Column

![[HGPI Policy Column] (No. 65) From the Dementia Project “The Future of Dementia Research Co-created with affected parties, Vol.3: A Stage Theory of Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) in Medical Research on Dementia and Commentary and Recommendations on PPI Evaluation”](https://hgpi.org/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/HGPI_20251027_PPI-in-Medical-Research-on-Dementia.png)

<POINTS>

- The idea of “full involvement” as the ideal form of PPI is unrealistic when considering the nature of dementia and its progression ad well as the burden placed on people living with dementia and their families; flexible forms of involvement should be taken into account.

- In international context, the formalization of PPI has been identified as a major challenge. In Japan as well, it is necessary to consider diverse and gradual forms of participation rather than focusing solely on full involvement.

- It is necessary to explore more optimal forms of PPI in which people living with dementia, their families and carers can be involved in research; therefore, it is expected that tools and methods for organizing levels and forms of involvement in the research process and appropriately evaluating their content will be developed.

In a previous installment of this column from the Dementia Project, we introduced the Person-Centered Care (PPC) approach utilized for Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) in Sweden. We mentioned that the PPC approach is a humanistic approach to healthcare which values the person behind the label of “patient” and that emphasizes their dignity and happiness, and that it provides valuable insights on how we can achieve sustainable PPI in domestic dementia research. For details, please see the related articles linked at the end of this column.

In this installment, we will share insights on the nature of multilayered involvement based on points identified over the course of discussions on PPI in dementia research held at Health and Global Policy Institute (HGPI).

Issues surrounding PPI evaluation

One example of how PPI is defined comes from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED), which recognizes it as, “Initiatives in which researchers refer to the knowledge of patients and the public in the medical research and clinical trial processes to produce research results that are more useful for patients and the public.”(AMED, 2025) While there are differences in recognition toward the concept of PPI or its definition among countries, they have a shared view of the ideal form of PPI as, “Involvement of patients and the public from when the research process begins to when it ends.” In this essay, we will refer to this as “full involvement.”

Just how realistic is that ideal form of PPI? Let us begin by examining situations in which people living with dementia are involved in research. If we say that it is not PPI if people living with dementia are not involved in research from start to finish, we then must ask if this form of PPI could be called realistic. While there are a variety of underlying diseases that cause dementia, conditions like Alzheimer’s disease are progressive in nature and dementia symptoms can result in impaired ability to think. Given these characteristics, we are left with the question if “full involvement” is truly the ideal form of the meaningful involvement in dementia research that we hope to achieve. The same can be said for the involvement of family members of people living with dementia or others close to them. If they wish to be involved in research as a form of social participation while supporting or providing long-term care to people living with dementia, the amount of time they can devote to such involvement is extremely limited. Among participants who are involved in their capacity as parties who have completed caregiving, those who are senior citizens themselves may experience physical or mental burdens due to the long hours or long periods of time required for involvement. As such, pursuing “full involvement” without considering the burdens or restrictions placed on patients or the public may not only encumber researchers while they are conducting studies, barriers like those discussed above may result in the exclusion of people who genuinely want to be involved.

Priority Goal 4 of the first Basic Plan for the Promotion of Policies on Dementia approved by Cabinet Decision on December 3, 2024 is The public can make effective use of new knowledge and technologies related to dementia,” and evaluation indicators for that Goal include:

- Process indicator: “Number of plans for research projects on dementia that are supported or conducted by the Government and that reflect the opinions of people living with dementia, their families, or others close to them”

- Output indicator: “Number of research projects related to dementia that are supported or conducted by the Government and that reflect the opinions of people living with dementia, their families, or others close to them”

- Outcome indicator: “Number of results from research projects related to dementia supported or conducted by the Government that are implemented throughout society”

In the midst of these practical issues, what conditions must PPI in dementia research meet before we can say, “This dementia study has PPI”? If we base this on current attitudes toward PPI, patients and the public would have to be involved from the start of the research process to its end before we could say that their opinions were reflected. However, adopting such a requirement could severely limit the number of people living with dementia, family members, and other people close to them who can take part in PPI.

Necessary actions for creating realistic and flexible evaluation indicators

One issue that HGPI has observed in past surveys of countries leading the way in PPI is preventing involvement from becoming a mere formality. Some are particularly concerned that requiring all researchers to implement “full involvement” or making its inclusion mandatory can contribute to the reduction of PPI to a formality. When promoting the widespread adoption of PPI in domestic dementia research, rather than placing the sole focus on “full involvement,” we may have to build frameworks that can appropriately evaluate more flexible and diverse forms of involvement.

Since around 2020, organizations that have produced innovative examples of PPI such as the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) in the United Kingdom have been using a more comprehensive and expansive concept called Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement (PPIE). As mentioned earlier, PPI refers to collaborative intervention in which patients and the public work alongside researchers in activities like planning, design, and implementation and take part in decision-making throughout the entire research process. Meanwhile, PPIE includes “engagement,” in which knowledge and research findings are shared with society and two-way dialogue is encouraged. PPIE refers to an approach in which involvement and engagement are integrated, in which researchers work with patients and the public to advance research, and in which greater emphasis is placed on two-way dialogue, the sharing of knowledge, and the creation of partnerships throughout the entire research process. In recent literature, PPIE has been positioned as a non-hierarchical and inclusive approach to the entire research cycle that engages researchers, patients, the public, and others as equal partners in continuous collaboration to realize mutual benefits (Lu et al., 2025). In other words, it can be viewed as a concept in which patients and citizens are not only involved in research decision-making and in which emphasis is placed on creating value through bilateral connections between researchers and people living with dementia, their families, others close to them, and society at every stage of the research process.

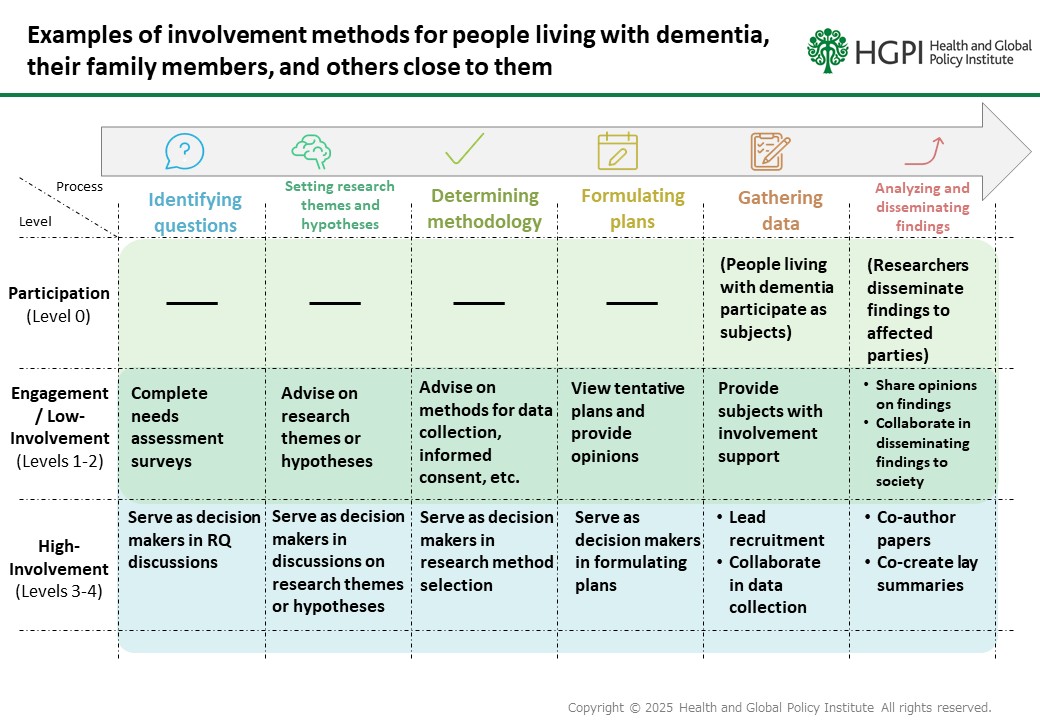

Based on approaches like these, for PPI to be implemented in dementia research in Japan, how must we define what forms of involvement are PPI? And what steps must be taken to evaluate PPI practices? To assist concrete discussions on these issues, the author and other members of HGPI have outlined involvement in the table below to show how it might take place over a simplified research process.

In this table, we have placed involvement level on the vertical axis and research process on the horizontal axis to show forms of involvement that are likely to take place during each process. Some assert that in theory, a clear distinction should be made between engagement and involvement, but others argue that instead of drawing a clear line between these two concepts, it is more realistic to understand them as a spectrum. This essay supports the latter stance in which there is a gradation, and thus categorizes involvement into three levels: Participation, Engagement/Low-Involvement, and High-Involvement.

One publication related to the above figure is the Japan Dementia Working Group’s “Handbook for Promoting Dementia Policies Together With People Living With Dementia,” which shows what forms of involvement from people living with dementia are necessary at which stages of the policy-making process. In dementia research, similar steps must be taken to specify what forms of involvement are necessary and at which stages.

The table shown above is only intended to provide suggestions in the context of this essay, and multiple in-depth discussions on this topic must be held in the future. We must ascertain what forms of PPI are most appropriate for people living with dementia, family members, and others close to them to be involved in research, and this will require identifying levels and forms of involvement for each research process and developing methods to appropriately evaluate involvement content. Levels and forms of involvement that are ideal for people living with dementia will always differ from those of their family members and others close to them. All aspects of involvement should be evaluated for each step in a manner that is expansive and that reflects real-world circumstances, and I believe it will be important to do so with the premise that involvement is a spectrum. As a suggestion, it will be useful to introduce methods of portraying PPI using a matrix like the table shown in this essay, with research processes on the horizontal axis and degree of involvement on the vertical axis.

In the future, we hope to see discussions deepened on realistic and effective measures or methods to promote or evaluate PPI that are more well-suited to the context of domestic dementia research, and that practical examples and evaluation frameworks from Japan and overseas are referred to when those discussions are held. In our capacity as a hub, HGPI would like to continue deepening those discussions for stakeholders in this area, centered on people living with dementia, their family members, people close to them, and researchers.

Reference

- Clare Wilkinson, Andy Gibson, Michele Biddle, Laura Hobbs, Public involvement and public engagement: An example of convergent evolution? Findings from a conceptual qualitative review of patient and public involvement, and public engagement, in health and scientific research, PEC Innovation, Volume 4, 2024, 100281, ISSN 2772-6282, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pecinn.2024.100281

- Gray R, Pipatpiboon N, Bressington D. How Can We Enhance Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement in Nursing Science? Nurs Rep. 2025 Mar 20;15(3):115. doi: 10.3390/nursrep15030115. PMID: 40137688; PMCID: PMC11944329.

- Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development. “AMED’s Approach to Patient and Public Involvement (PPI)”.April, 2025, https://www.amed.go.jp/en/ppi/ppiconcepten.html

- Lu, W., Y. Li, C. Evans, et al. 2025. Evolution of Patient and Public Involvement and Engagement in Health-Related Research: A Concept Analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.70140.

Column author

Nana Moriguchi (Associate, Health and Global Policy Institute)

Top Research & Recommendations Posts

- [Policy Recommendations] The Path to a Sustainable Healthcare System: Three Key Objectives for Public Deliberation (January 22, 2026)

- [Research Report] The 2025 Public Opinion Survey on Healthcare in Japan (March 17, 2025)

- [Research Report] Perceptions, Knowledge, Actions and Perspectives of Healthcare Organizations in Japan in Relation to Climate Change and Health: A Cross-Sectional Study (November 13, 2025)

- [Policy Recommendations] Reshaping Japan’s Immunization Policy for Life Course Coverage and Vaccine Equity: Challenges and Prospects for an Era of Prevention and Health Promotion (April 25, 2025)

- [Research Report] AMR Policy Update #4: Cancer Care and AMR (Part 1)

- [Research Report] The 2023 Public Opinion Survey on Satisfaction in Healthcare in Japan and Healthcare Applications of Generative AI (January 11, 2024)

- [Public Comment Submission] “Assessment Report on Climate Change Impacts in Japan (Draft Overview)” (December 24, 2025)

- [Research Report] The 2026 Public Opinion Survey on Healthcare in Japan (February 13, 2026)

- [Policy Recommendations] Developing a National Health and Climate Strategy for Japan (June 26, 2024)

- [Research Report] The Public Opinion Survey on Child-Rearing in Modern Japan (Final Report) (March 4, 2022)

Featured Posts

-

2026-01-09

[Registration Open] (Hybrid Format) Dementia Project FY2025 Initiative Concluding Symposium “The Future of Dementia Policy Surrounding Families and Others Who Care for People with Dementia” (March 9, 2026)

![[Registration Open] (Hybrid Format) Dementia Project FY2025 Initiative Concluding Symposium “The Future of Dementia Policy Surrounding Families and Others Who Care for People with Dementia” (March 9, 2026)](https://hgpi.org/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/dementia-20260309-top.png)

-

2026-02-05

[Registration Open] (Webinar) The 141st HGPI Seminar “Current Status and Future Prospects of Korea’s Obesity Policy: Voices of People with Lived Experience in Policy Promotion” (March 3, 2026)

![[Registration Open] (Webinar) The 141st HGPI Seminar “Current Status and Future Prospects of Korea’s Obesity Policy: Voices of People with Lived Experience in Policy Promotion” (March 3, 2026)](https://hgpi.org/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/hs141-top-1.png)