[Event Report] The 48th Special Breakfast Meeting – The COVID-19 Response and Considering Health Policy From 2040 (September 12, 2022)

![[Event Report] The 48th Special Breakfast Meeting – The COVID-19 Response and Considering Health Policy From 2040 (September 12, 2022)](https://hgpi.org/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/sbm-48-1-top_035_MG_2106-1.jpg)

For the 48th Special Breakfast Meeting, we hosted Mr. Kazuhito Ihara, Director-General of the Health Insurance Bureau at the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare and a leading figure in Japan’s response to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic as Director-General of the Health Policy Bureau until June 2021. Mr. Ihara gave a lecture on healthcare policy with a focus on demographic changes that will occur in Japan by 2040.

Key points of the lecture

- Based on the issues in the healthcare provision system that came to light during the response to COVID-19, to be prepared for the next infectious disease threat, a proposal for revising the Infectious Disease Act is likely to be submitted during the extraordinary Diet session this autumn.

- It is projected that by 2040, the growth of Japan’s elderly population will begin to decelerate and the number of working-age adults will rapidly decline, so it will be important to take action to address challenges presented by manpower shortages and a declining population. Industry, Government, academia, and civil society must work to reform the healthcare provision system to respond to circumstances in each region while keeping a steady eye on how healthcare demand will change by 2040.

Healthcare provision system issues that surfaced during the COVID-19 response

Healthcare provision system issues that surfaced during the COVID-19 response

Looking at daily new confirmed cases of COVID-19 per million people (7-day rolling average) among G7 members, as of August 27, 2022, Japan has the most new cases. However, this is the result of restrictions on events and daily activities being removed or eased, and the number of domestic daily new confirmed cases is still significantly lower than peaks in other countries between December 2021 and January 2022. As of August 2022, Japan has over 250,000 daily new confirmed cases, but considering the fact that a large outbreak of influenza can result in around 300,000 new cases per day, we can say that infections this summer have roughly been on par with influenza.

There was a sharp increase in daily new confirmed COVID-19 deaths per million people (7-day rolling average) in February 2020, when the pandemic was in its early stages. There was another sharp increase in winter 2021. Although vaccine development was originally predicted to take three to four years, COVID-19 vaccines were deployed after about one year. The vaccines were a game-changer that led to a dramatic reduction in global COVID-19 deaths.

Meanwhile, looking at cumulative number of excess deaths per million people (since January 1, 2020), we see that Japan had negative excess mortality throughout the early stages of the pandemic until early this year, then later had positive excess mortality as the number of deaths increased alongside the number of people infected, mainly among elderly people and people with underlying diseases. Compared to other G7 countries, however, Japan has consistently maintained a low number of deaths.

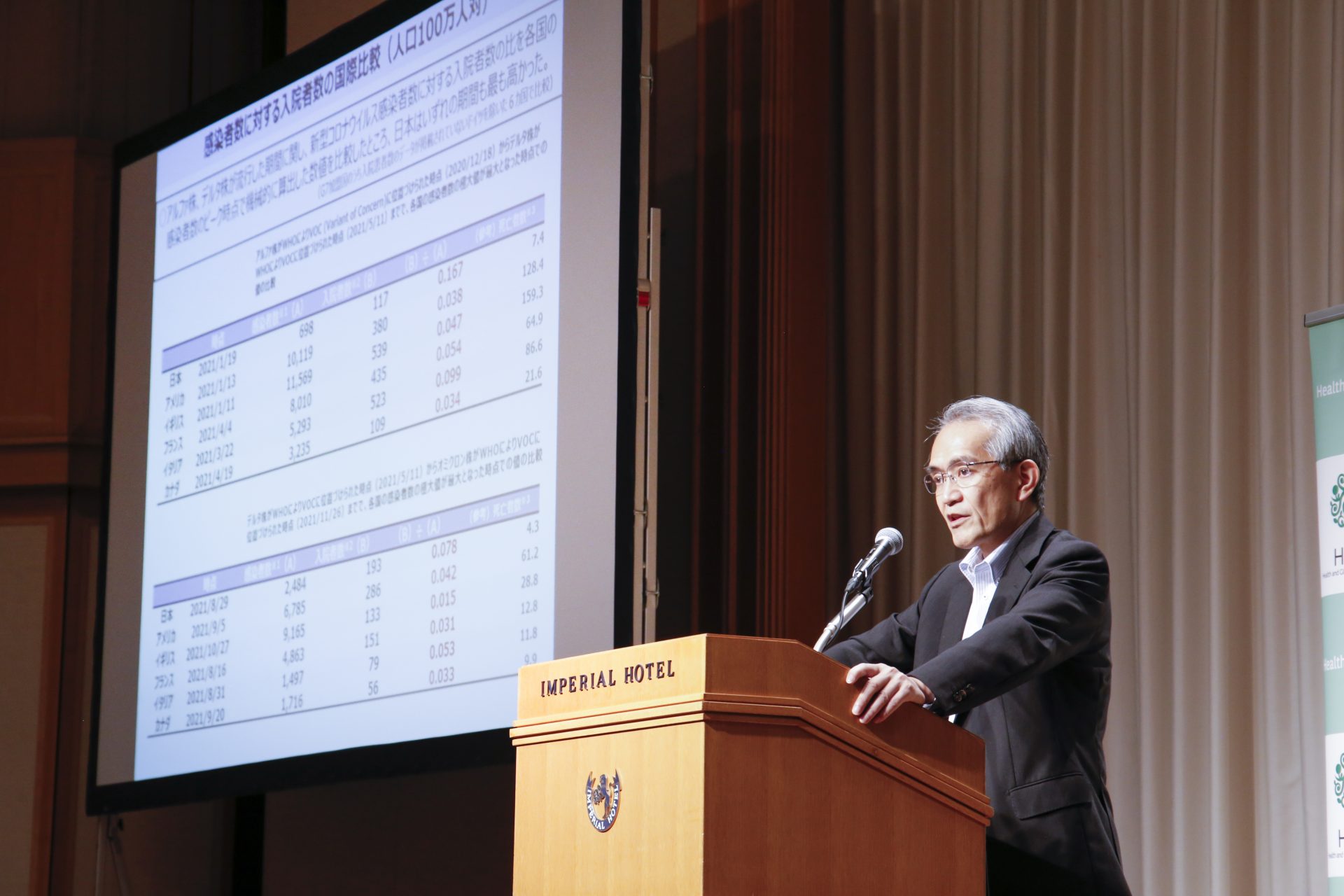

Furthermore, in an international comparison of the ratio of hospitalizations to the number of COVID-19 infections per million people using automatically calculated data from the periods each country reached peak infection rates with the alpha and delta variants, Japan was found to have the highest ratio of hospitalizations to number infections during both periods. (This comparison was conducted among six G7 members, as data on hospitalizations in Germany was not released.) Although Japan experienced problems during the COVID-19 pandemic in which hospitals were unable to admit people due to care bed shortages, as far as we can see from this data, Japan hospitalized relatively more infected people than other G7 countries.

Looking back, we can point out the following three issues for the healthcare provision system during the COVID-19 pandemic response.

When COVID-19 was rapidly spreading, patients with fevers could not get tested or be seen at outpatient fever clinics

- Preparations were insufficient, including those to secure PCR kits and other test kits; public health centers became overburdened; and family doctor services have been underutilized.

Despite the fact that Japan is one of the countries with the most hospitals and care beds, patients could not be hospitalized

- Japan was slow to begin operating a system for hospitalizations during the early stages of the pandemic; the number of hospitals that can receive COVID-19 patients, including those with severe symptoms, is limited; and healthcare institutions (including logistics support hospitals and similar institutions) do not engage in sufficient role-sharing and collaboration.

Insufficient digitization and visualization

- Certain practices made it time-consuming to grasp the overall situation. For example, information on patients who tested positive at outpatient fever clinics was submitted by fax.

When infections peaked during the fifth wave in summer 2021, only people with moderate to severe symptoms could be hospitalized. Because managing issues like respiratory failure usually requires four or more nursing staff per patient, their numbers were insufficient to provide care for people with moderate to severe symptoms at existing Intensive Care Units (ICUs) and other facilities. A portion of 7:1 beds were closed so staff could be rotated to COVID-19 beds and, as a result, 1.25 beds were closed for every COVID-19 bed added.

Last summer, approximately 12,000 beds were secured in Tokyo and surrounding three prefectures. Taking the number of beds that were closed into account (approximately 15,000), the total number of beds converted to COVID-19 beds was approximately 27,000. This is equivalent to 25% of the 110,000 care beds rated 7:1 or higher in Tokyo and the surrounding three prefectures, which resulted in severe restrictions to standard medical care. Based on these experiences, at the end of last year, the Kishida Cabinet formulated a comprehensive plan to achieve a 30% increase in hospital admissions by further increasing the number of hospital beds and raising occupancy rates.

On June 17, 2022, the COVID-19 Task Force presented a decision that set a direction for preparations for the next infectious disease threat, stating that a framework should be established by law which allows prefectures and healthcare institutions to form agreements during non-emergency periods to provide care beds and other measures for managing emerging infectious diseases and to ensure the healthcare provision system can respond rapidly during the early stages of outbreaks. It also stated that measures must be considered for ensuring actions are taken in accordance with those agreements during an infectious disease outbreak or similar event. These measures include publicizing the status regarding the implementation of said agreements; creating systems for compensating certain healthcare institutions for income losses incurred by continuing services during early stages of infectious disease outbreaks; providing recommendations and instructions from prefectural governors; and withdrawing approval from special function hospitals.

The impact of the demographic shift on social security in 2040

The impact of the demographic shift on social security in 2040

- Changes in society as we approach 2040

The number of outpatient visits (for both health care insurance and publicly funding care) is projected to decline from 7.69 million per day in 1989 to 7.53 million per day in 2040, while the number of inpatient visits (for both health care insurance and publicly funding care) is expected to increase from 1.28 million per day in 1989 to its peak at 1.40 million per day in 2040, mainly due to inpatient visits for elderly people.

According to “Population Projections for Japan (Medium-fertility and medium-mortality)” from the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, the growth rate of the population for people age 65 and over by 2040 will remain low, at 0.1% to 0.9%. Although there will be a temporary increase in the growth rate of the population that is age 75 and over for a few years starting in 2022 (when members of the baby boomer generation enter their late elderly years), that rate is expected to be negative in the 2030s.

Since around 1998, there has been a negative growth rate in the population for people ages 15 to 64. This decline in young people is a major factor that defines Japan’s economy and society. Reforming social security to achieve a sustainable society as the population declines has become a key theme.

- The imbalance between benefits and burdens in social security

Looking at past trends and predicted changes in social security benefits as a percentage of GDP in the years leading up to 2040, we see that social security benefits paid by Japan rose by 6.8% of GDP from 2000 to 2015. Over the past fifteen years, members of the baby boomer generation began drawing pensions and the number of elderly people increased by 53.7%, or 11.83 million people. However, for the fifteen-year period from FY2025 to FY2040, it is projected that social security benefits as a percentage of GDP will increase by only 2.1% to 2.2%.

According to reference materials released on November 8, 2021 by the Fiscal System Council’s Sectional Subcommittee on Financial System regarding the state of benefits and burdens in social security, compared to other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) members, Japan is maintaining “medium welfare, low burden” conditions in which benefits and burdens are imbalanced. Moving forward, per capita healthcare spending and the rate at which people are certified as requiring support or long-term care will increase significantly as the population ages, so this imbalance is expected to continue to grow. It is urgent that reforms are introduced to ensure Japan’s social security system is sustainable.

- Necessary actions for overcoming manpower shortages and population decline

For the three decades of the Heisei era, from 1989 to 2019, there was significant growth in employment rates among women and elderly people. This meant it was possible to maintain job numbers and the size of the labor force at late 1990s levels even with a declining population. In 2018, the health and welfare sector accounted for 8.26 million of Japan’s 66.65 million workers. This is equivalent to approximately 12% of the labor force or one in eight workers. If current trends continue, the health and welfare sector will require approximately one in five workers by 2040. In the future, along with increasing the size of the labor force, steps must be taken so operations in health and welfare settings can be performed with fewer people. It will be important to continue advancing initiatives that aim to create an environment for a more diverse workforce and social participation, extend healthy life expectancies, enhance productivity by reforming health and welfare services, and review benefits and burdens to ensure the social security system is sustainable.

- An example of utilizing technology to improve productivity in long-term care services

Social Welfare Corporation Zenkoukai (based in Ota City, Tokyo) has introduced wellness monitoring sensors and digital recording apps at its special nursing homes for the elderly and day care facilities for quality assurance in care and to enhance operational efficiency. While most special nursing homes for the elderly have about one caregiver for every two residents, utilizing the aforementioned wellness monitoring sensors and information and communications technology (ICT), the Zenkoukai FLOS Higashi-Kojiya facility was able to increase the number of residents per caregiver from 1.9 in 2015 to 2.8 today. Initiatives such as these have made it possible to reach average annual salaries of 4.8 million yen for their staff, which is higher than the Tokyo average for special nursing home staff (which is approximately 4.2 million yen).

Although health data reform still faces many issues, we can commend the fact that dramatic progress in online healthcare was achieved during the COVID-19 pandemic. In the future, I think it will be important to build systems that enable individual health institutions to share various types of health and medical information with other institutions and organizations.

Changes in healthcare demand and challenges facing the healthcare provision system as we approach 2040

Changes in healthcare demand and challenges facing the healthcare provision system as we approach 2040

- Care areas in every region will experience a simultaneous decrease in the elderly population and rapid decrease in the working-age population

According to “Regional Population Projections for Japan: 2015-2045 (2018)” from the National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, many care areas will see a simultaneous decrease in the number of both elderly people and working-age people as we approach 2040. From 2015 to 2025, many secondary care areas will experience an increase in the number of people age 65 years and over and a decrease in the working-age population. However, from 2025 to 2040, the population age 65 years and over will grow in 132 care areas and shrink in 197 care areas. Furthermore, many areas will experience a sharp decline in the working-age population.

- Outpatient visits are already declining in many care areas

Examining changes in healthcare demand, we see there is already a decline in outpatient visits in many care areas. It is projected that the number of outpatient visits nationwide will peak in 2025, and the percentage of those visits made by people age 65 years and over is projected to continue to rise to approximately 60% in 2040. Furthermore, the number of outpatient visits had already peaked in 217 care areas by 2015.

- Inpatient visits are on the rise and will peak by 2035

The number of inpatient visits is still trending upwards but will peak by 2035. Nationwide, inpatient visits are expected to peak in 2040. The percentage of hospitalized people age 65 years and over is expected to continue increasing to reach approximately 80% of hospitalizations by 2040.

- The number of people receiving in-home care will increase in many regions and the need for combined health and long-term care will grow

In the future, the number of people receiving in-home care will increase in many regions. Nationwide, their number is projected to peak after 2040. There will also be greater need for combined health and long-term care.

- Issues related to the healthcare provision system

Issues facing the healthcare provision system that were brought to the forefront during the COVID-19 pandemic included: responding to people during the highly acute phase (especially in terms of human resources); duty-sharing and collaboration among healthcare institutions (including information-sharing); responding to the needs of people recuperating at home (i.e., acute phase in-home care); and digitalization and visualization.

Various measures are required to respond to Japan’s changing demographics due to super-aging and population decline. These include addressing manpower constraints caused by a shrinking working-age population; securing and maintaining healthcare services in regions facing population decline; implementing work style reform for physicians; responding to changing demands for healthcare due to super-aging and the advance of population decline; and meeting an increase in demand for combined health and long-term care services and end-of-life care (especially in urban areas).

After sharing such issues, it will be important to advance policies in several areas, including: reinforcing acute services with infectious disease response in view; strengthening forms of care that support integrated community care, namely inpatient, outpatient, and in-home care; securing and maintaining health services in areas facing population decline; promoting collaboration among healthcare institutions; promoting efforts to utilize regional medical coordination promotion corporations; promoting task-sharing and shifting; promoting team treatment; promoting digital transformation (DX) and the implementation of AI and ICT; and implementing health data reform.

Policy schedule and the collaboration needed from industry, Government, academia, and civil society

Below are items on the policy schedule for this year and next.

Items related to the healthcare provision system

- Revision of the Infectious Diseases Control Law (to reinforce the healthcare provision system)

- Eighth revision of the Medical Care Plan (to be formulated in 2023 and come into effect in 2024)

- Establishing a system for providing family doctor services

- Enforcing physician work style reforms (in 2024)

- Healthcare DX (for medical information sharing and medical service fee DX)

Items related to health insurance

- Annual drug price revision (2023)

- Simultaneous revision of medical and long-term care service fees (2024)

- Increase of Childbirth and Childcare Lump-sum Grants (2023)

- Institutional reforms (revising insurance premiums, including those for the high-income insured; enacting the Medical Cost Optimization Plan)

The Pharmaceutical Industry Vision 2021, which was compiled in September 2021, aims to contribute to the extension of healthy life expectancies and industrial and economic development through innovative drug discovery as well as to ensure the quality and stable supply of pharmaceuticals to leave the next generation a society where people can receive high-quality medical care with peace of mind. Pharmaceutical spending increased from approximately 9.2 trillion yen in 2015 to approximately 10.1 trillion yen in 2019 and continues to rise, and there are issues facing initiatives for innovative pharmaceuticals (such as the proactive introduction of research assets from academia and venture firms, and meeting unmet medical needs), generic pharmaceuticals (ensuring quality and stable supplies), and pharmaceutical distribution (ensuring stable supplies and a sound health market structure). As these diverse issues continue to pile up, society must engage in opinion exchanges with multi-stakeholders while being mindful of the policy schedule.

A lively opinion exchange was held during the audience Q&A session after the lecture. Topics included financial resources for future social security benefits and improving efficiency in the healthcare provision system.

(Photographed by: Kazunori Izawa)

■Profile

Mr. Kazuhito Ihara (Director-General, Health Insurance Bureau, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare)

Mr. Kazuhiro Ihara graduated from the University of Tokyo Faculty of Law in 1987. He joined the former Ministry of Health and Welfare that same year, where he built experience at every department. His past responsibilities include establishing the Long-Term Care Insurance System, health insurance reform, countermeasures for Japan’s declining birthrate, establishing the new system of welfare for people with disabilities, addressing issues with pension records, and formulating the Act on Medical Care for Patients with Intractable Diseases. Outside of his roles at the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, he has also served at Itami City Hall, JETRO New York, the Prime Minister’s official residence, and the Japan Pension Service. After serving as Director-General for Policy Planning and Coordination and Director-General of the Health Policy Bureau, he assumed his current position in June 2022.

Top Research & Recommendations Posts

- [Research Report] Perceptions, Knowledge, Actions and Perspectives of Healthcare Organizations in Japan in Relation to Climate Change and Health: A Cross-Sectional Study (November 13, 2025)

- [Policy Recommendations] Reshaping Japan’s Immunization Policy for Life Course Coverage and Vaccine Equity: Challenges and Prospects for an Era of Prevention and Health Promotion (April 25, 2025)

- [Research Report] The 2025 Public Opinion Survey on Healthcare in Japan (March 17, 2025)

- [Research Report] The 2026 Public Opinion Survey on Healthcare in Japan (February 13, 2026)

- [Research Report] 2019 Survey on Healthcare in Japan

- [Research Report] Building a Mental Health Program for Children and Measuring its Effectiveness (June 16, 2022)

- [Policy Recommendations] Developing a National Health and Climate Strategy for Japan (June 26, 2024)

- [Research Report] The Public Opinion Survey on Child-Rearing in Modern Japan (Final Report) (March 4, 2022)

- [Research Report] The 2023 Public Opinion Survey on Satisfaction in Healthcare in Japan and Healthcare Applications of Generative AI (January 11, 2024)

- [Policy Recommendations] Mental Health Project: Recommendations on Three Issues in the Area of Mental Health (July 4, 2025)

Featured Posts

-

2026-01-09

[Registration Open] (Hybrid Format) Dementia Project FY2025 Initiative Concluding Symposium “The Future of Dementia Policy Surrounding Families and Others Who Care for People with Dementia” (March 9, 2026)

![[Registration Open] (Hybrid Format) Dementia Project FY2025 Initiative Concluding Symposium “The Future of Dementia Policy Surrounding Families and Others Who Care for People with Dementia” (March 9, 2026)](https://hgpi.org/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/dementia-20260309-top.png)

-

2026-02-27

[Registration Open] (Webinar) The 142nd HGPI Seminar “World Kidney Day 2026” Theme in Focus: The Current State of Green Nephrology and Green Dialysis—Balancing Kidney Health and Planetary Health (March 10, 2026)

![[Registration Open] (Webinar) The 142nd HGPI Seminar “World Kidney Day 2026” Theme in Focus: The Current State of Green Nephrology and Green Dialysis—Balancing Kidney Health and Planetary Health (March 10, 2026)](https://hgpi.org/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/The142nd_HGPI_Seminar.jpg)

-

2026-03-03

[Registration Open] Online Seminar “Implementing Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) Measures into Society: Towards a Data-Driven Health System” (April 21, 2026)

![[Registration Open] Online Seminar “Implementing Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) Measures into Society: Towards a Data-Driven Health System” (April 21, 2026)](https://hgpi.org/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/HGPI_20260421_CKDonlineseminar-.png)