[Event Report] The 91st HGPI Seminar – Developing Foundational Health Policy for Promoting Women’s Empowerment and Removing the Barriers Facing Women and Young People (December 17, 2020)

date : 2/9/2021

Tags: HGPI Seminar, Women's Health

![[Event Report] The 91st HGPI Seminar – Developing Foundational Health Policy for Promoting Women’s Empowerment and Removing the Barriers Facing Women and Young People (December 17, 2020)](https://hgpi.org/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/91st_en.jpg)

For the 91st HGPI Seminar, we hosted Dr. Kyoko Tanebe, who is a gynecologist and serves as Representative Director of Women’s Clinic We! TOYAMA and as a member of the Toyama Prefectural Assembly. From the perspective of health policy for promoting the advancement of women, Dr. Tanabe spoke about information we should know about women’s bodies and on the relationship between women’s health and the social environment surrounding women.

Key points of the lecture

- Support for women’s health should be promoted in parallel to efforts to promote women’s empowerment and participation.

- A life-course approach[1] that provides women correct information from childhood and adolescence and teaches them to think and make decisions with adulthood and old age in mind is important to address the various health issues women face at different life stages.

- Sex education in Japan currently lacks content related to fertility and how to avoid domestic violence (DV). Such topics are related to personal dignity and are necessary for women to be educated on so they can make fulfilling life plans. We must review the structure and content of sex education.

■The current state of society surrounding women in Japan

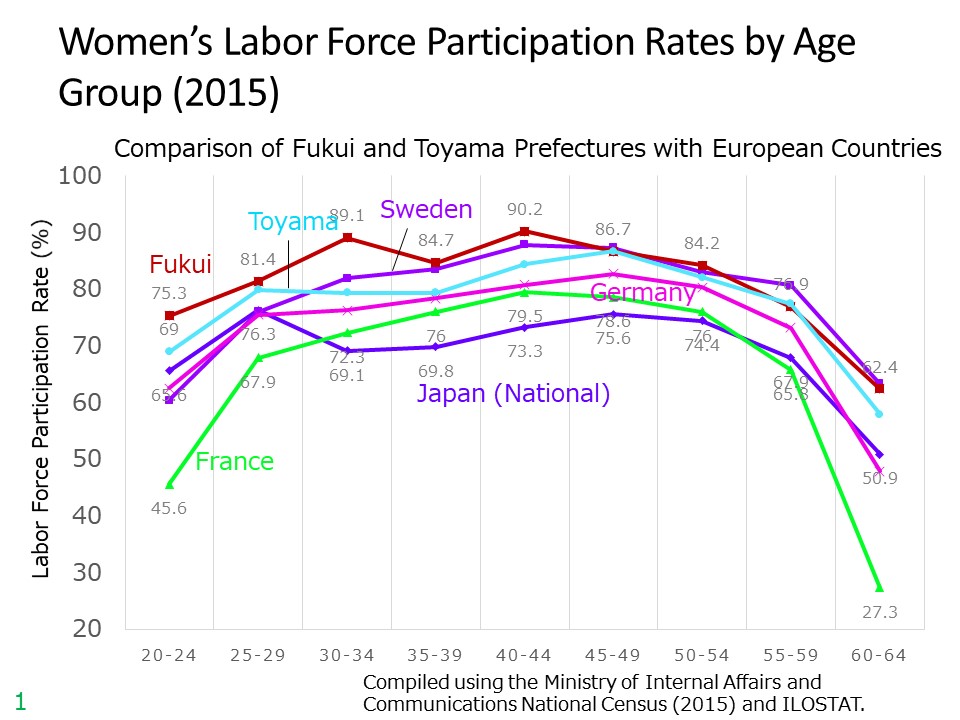

To offset labor shortages accompanying accelerating population decline and to secure a sufficient quantity of labor, efforts are underway in Japan to draw out the potential of women as a source of labor and encourage more workforce participation among women. Until now, labor force participation for Japanese women has followed an M-shaped curve with the dip occurring during pregnancy, childbirth, and child rearing. Meanwhile, in Scandinavian countries like Sweden, women’s labor force participation rates are extremely high and they remain high during pregnancy, childbirth, and child rearing. Based on excellent precedents like Sweden, Japan is promoting policies related to gender equality to increase the labor force participation rate among women. In addition to securing a sufficient quantity of labor, Japan must also improve its workforce quality to increase overall productivity. Promoting the active participation of women in the workforce will enable women to focus on new fields that have been overlooked in Japan’s male-dominated society. This will result in various innovations originating from women’s fresh perspectives. To achieve this, it will be crucial to involve many women in decision-making to improve workforce quality and create a better future for Japan.

The M-shaped curve in women’s labor force participation rate has already been eliminated in certain prefectures like Fukui and Toyama, where women’s labor force participation rates are as high as those in Northern European countries. However, if we look at the progress of women’s advancement in regions with high labor force participation rates, we cannot say that women are fully participating in decision-making roles such as in management. For example, women’s ratios in management positions in companies, as members of prefectural assemblies, and as presidents of residents’ associations are very low in the Hokuriku region. Although the employment rate for women is high, stereotypes concerning gender roles remain strong.[2] Even though women are filling all types of roles at the workplace, in homes, and in communities, stereotypes are preventing them from being able to participate in decision-making. In addition, it has been shown among OECD countries, women in Japan get the least amount of sleep.[3] The concentration of many roles on women suggests that women are being forced to expend their own health to live their daily lives. A society in which women cannot play active roles without having to sacrifice or give up on anything is not a society in which women’s empowerment and participation can be truly promoted.

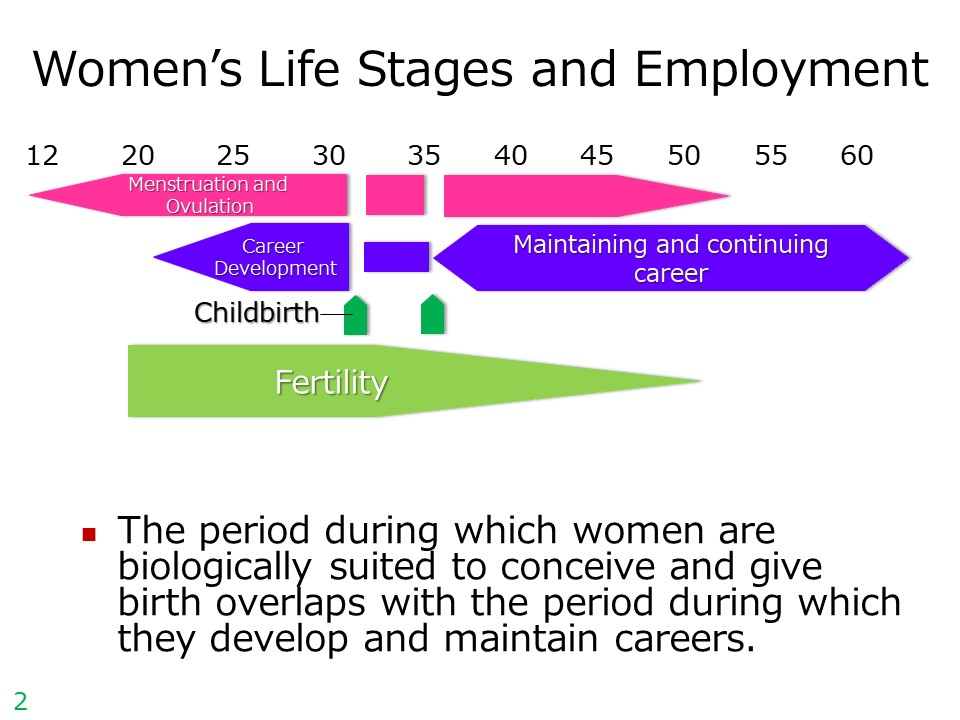

Furthermore, examining willingness to seek promotions among women who have recently entered the workforce and are at the beginning of their active roles in society, motivation was trending upwards until around 2011 but has declined in recent years. Meanwhile, the number of women who do not want to be in management positions has increased. One of the reasons behind this is rooted in the fact that the ages when people develop their careers coincides with the ages women’s fertility[4] is the highest, meaning that women must make a trade-off between career advancement and having children. In addition, in Japan, where the prevailing attitude is that women must have children after marriage, an increasing number of women are choosing to either avoid or postpone marriage to escape public pressure to have children after marriage This has resulted in a decline in the marriage rate. To improve this situation, women must be provided with opportunities to learn about women’s health so that they can establish their own life plans, and efforts to promote women’s empowerment and participation in society and efforts to support women’s health must be packaged together.

■The importance of establishing a life course approach to overcome women’s health issues

As described below, women are at risk to health problems due to a variety of factors, such as (1) health issues specific to women; (2) health issues caused by social determinants; and (3) health issues related to reproductive health.[5] Furthermore, the health issues women face vary significantly by life stage, which is why it is important for women to be provided with comprehensive support based on a life course approach that considers the various diseases or risks that occur throughout early childhood, adolescence, adulthood, and late adulthood, and to encourage preventive action.

- Health issues specific to women

Fluctuations in hormone levels during the menstrual cycle have significant impacts on physical and mental health. Women also face the risk of contracting diseases caused by female sex hormones including dysmenorrhea, endometriosis, and uterine fibroids. Not only do female sex hormones have various effects on physical and mental health from puberty to sexual maturity, women also face health issues when female sex hormones rapidly decline and disappear during and after menopause. These issues include menopausal disorders, osteoporosis, dementia, and frailty.[6]

- Health issues caused by social determinants

Many young women are underweight and have very poor nutrition as a result of excessive dieting. Insufficient nutrition during one’s youth can lead to poor future health, particularly once one reaches old age. Specifically, insufficient nutrition can lead to locomotive syndrome[7] and frailty. There is also data suggesting that women are more likely than men to develop depression and addictions. Issues like premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD), menopausal syndrome, and postpartum blues are more likely to appear when a woman is in a weakened physical or mental state such as during the premenstrual, postpartum, and menopausal periods, or is subjected factors causing high levels of stress such as DV, harassment, abuse, poverty, and isolation. Access to medical care during these periods makes it more likely that these symptoms can be controlled. However, there are cases in which women develop severe depression or postpartum depression when they do not receive the support they need.

- Health issues related to reproductive health

In general, women are more likely to experience the more severe symptoms of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), which can be the cause of serious reproductive health issues such as infertility or higher risk of complications during childbirth. In addition, cervical cancer caused by human papillomavirus (HPV) has significant impacts on safety and security during pregnancy, childbirth, and child rearing. Many women give up their plans for pregnancy and childbirth due to HPV infection, and HPV infection is a source of great concern related to childbirth and child rearing for many couples. It is important that policies are in place to help prevent diseases that are likely to occur during the most fertile years of women’s lives.

■Women’s health issues caused changes in modern lifestyle

The way women live their lives has changed dramatically over the past three decades. Compared to women 30 years ago, women today experience menarche earlier, have their first child later, and give birth fewer times over their lifetimes. This has resulted in far more menstrual cycles over the life course and an increase in gynecological diseases such as endometriosis. Endometriosis not only causes menstrual pain and pain during intercourse, it also leads to increased risk of infertility and cancer. Endometriosis also causes fertility to decline earlier, so women with endometriosis who want to have children must plan their lives in advance.

The increase in menstrual cycles experienced by modern women affects performance in the workplace in many ways. However, low-dose birth control can be used to prevent declines in performance. The pill thins the endometrium, a source of menstrual pain, bringing various benefits such as reduced menstrual pain, less blood loss, and better quality of life. However, compared to other countries, usage of the pill among Japanese women is still low, and information about the pill is still not widely available in Japan. Even if people are taught about the pill in junior high and high school, the information is difficult for them to relate to and few of them remember it. Educational opportunities should be provided to those who are at the age when they are about to join the workforce and start building a career so they can learn about the pill.

■Gaps in sex education in Japan

Sex education in Japan mainly focuses on contraception, unexpected pregnancy, and STDs. Little information is provided on (1) fertility and (2) avoiding DV. Knowledge on these topics is highly necessary for life planning.

(1) Fertility

Fertility changes dramatically as a woman ages. Even if someone ovulates and menstruates normally, egg number and quality rapidly declines after age 37, making it more difficult to conceive. Although more couples are undergoing fertility treatment, fertility treatment requires many hospital visits, making it difficult for working women to find time to visit treatment facilities or adjust their schedules. Balancing work and fertility treatment is also a source of mental strain. Women require knowledge about fertility and career planning so they can think realistically when creating life plans.

(2) Avoiding DV

DV refers to violence committed by a current or past partner in an intimate relationship, such as a spouse or lover. DV is not only limited to violence of a physical nature; it also includes psychological and sexual violence. Because psychological and sexual violence are often invisible, both the perpetrator and victim are often unaware that what is occurring constitutes DV. For example, not cooperating with a partner’s wishes to use contraception is a form sexual violence, while actions such as ignoring someone, shouting at them, and monitoring their e-mails are psychological violence. It can be difficult for a victim to escape from DV once a relationship of control has been established between the dating or married couple. Therefore, it is important to avoid DV during the earlier stages of relationships, such as during dating, and to prevent situations from which victims of DV cannot escape.

Knowledge about fertility and DV is essential for women to experience relationships and make life plans for marriage, childbirth, and balancing a career with child rearing. Sex education in Japan often turns a blind eye towards sex or treats sex as a forbidden topic. In the future, we must review the structure and content of sex education in Japan so women can acquire the knowledge they need to make fulfilling life plans.

[1] An approach in which disease and risk prevention during the prenatal period and early childhood are linked to health in adulthood and old age.

[2] The fixed division of roles based on gender, or deciding the roles of men and women based on fixed attitudes. For example, “Men should work and women should stay at home,” or “Men should handle central work tasks and women should handle supplementary ones.”

[3] Source: OECD Gender Data Portal: https://www.oecd.org/gender/data/OECD_1564_TUSupdatePortal.xlsx (Accessed January 21, 2021).

[4] The ability to conceive and bear children.

[5] Sexual and reproductive health.

[6] Weakening of the muscles or joints.

[7] The physical state of decreased mobility due to musculoskeletal system damage.

■ Profile

Dr. Kyoko Tanebe (Representative Director, Women’s Clinic We! TOYAMA; Member, Toyama Prefectural Assembly)

Dr. Tanebe graduated from the University of Toyama’s Faculty of Medicine in 1990 and Graduate School of Medicine and Pharmaceutical Sciences in 1998. After working at Toyama Medical and Pharmaceutical University Hospital and the Obstetrics and Gynecology Department at Aiiku Hospital, she became the director of the Women’s Clinic We! TOYAMA in 2006 and its Representative Director in 2019. Aiming to tackle issues facing society outside of the scope of medicine, she ran a successful campaign in Toyama Prefecture’s unified local elections and joined the Toyama Prefectural Assembly in April 2019. Her main positions include: Member, Special Committee on Intensive Policy, Council for Gender Equality, Cabinet Office; Executive Director, Toyama Medical Association; Standing Director, Japan Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; Vice Chairman, Public Service Promotion Committee, Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology; Member, Committee for Improving the Living Environments of Children, Japan Pediatric Society; and Board Member, Toyama Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Top Research & Recommendations Posts

- [Policy Recommendations] Reshaping Japan’s Immunization Policy for Life Course Coverage and Vaccine Equity: Challenges and Prospects for an Era of Prevention and Health Promotion (April 25, 2025)

- [Research Report] Perceptions, Knowledge, Actions and Perspectives of Healthcare Organizations in Japan in Relation to Climate Change and Health: A Cross-Sectional Study (November 13, 2025)

- [Research Report] The 2025 Public Opinion Survey on Healthcare in Japan (March 17, 2025)

- [Research Report] The 2026 Public Opinion Survey on Healthcare in Japan (February 13, 2026)

- [Research Report] 2019 Survey on Healthcare in Japan

- [Research Report] Building a Mental Health Program for Children and Measuring its Effectiveness (June 16, 2022)

- [Research Report] The Public Opinion Survey on Child-Rearing in Modern Japan (Final Report) (March 4, 2022)

- [Policy Recommendations] Developing a National Health and Climate Strategy for Japan (June 26, 2024)

- [Research Report] The 2023 Public Opinion Survey on Satisfaction in Healthcare in Japan and Healthcare Applications of Generative AI (January 11, 2024)

- [Policy Recommendations] Mental Health Project: Recommendations on Three Issues in the Area of Mental Health (July 4, 2025)

![[Registration Open] Online Seminar “Implementing Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) Measures into Society: Towards a Data-Driven Health System” (April 21, 2026)](https://hgpi.org/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/HGPI_20260421_CKDonlineseminar-.png)