[HGPI Policy Column] No. 9 – From the Dementia Policy Team – What Do Basic Acts Lead To? Creating Common Good in Civil Society

date : 4/1/2020

Tags: Dementia, HGPI Policy Column

![[HGPI Policy Column] No. 9 – From the Dementia Policy Team – What Do Basic Acts Lead To? Creating Common Good in Civil Society](https://hgpi.org/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/column-top-dementia-3.jpg)

Key points

・The meaning and role of basic acts has gradually changed over time.

・Expectations are high for the Basic Law for Dementia to build awareness in society and enable cooperation across ministries.

・The Basic Law for Dementia is just the beginning. Action looking towards the future after its enactment must be taken.

Introduction

In our previous column, we discussed creating publicness with the Basic Law for Dementia. Within that discussion, we considered the possibility that people with fewer connections to dementia are that much more important for the Basic Law for Dementia, and getting them involved requires a large legal framework that enables people to establish artificial relationships with communities they do not belong to. That framework is publicness. Nonpartisan discussions on the Basic Law for Dementia will begin in the future, so in this column, we would like to take another look at basic acts to prepare for future efforts in communicating the importance of enacting the Basic Law for Dementia.

What Are Basic Acts?

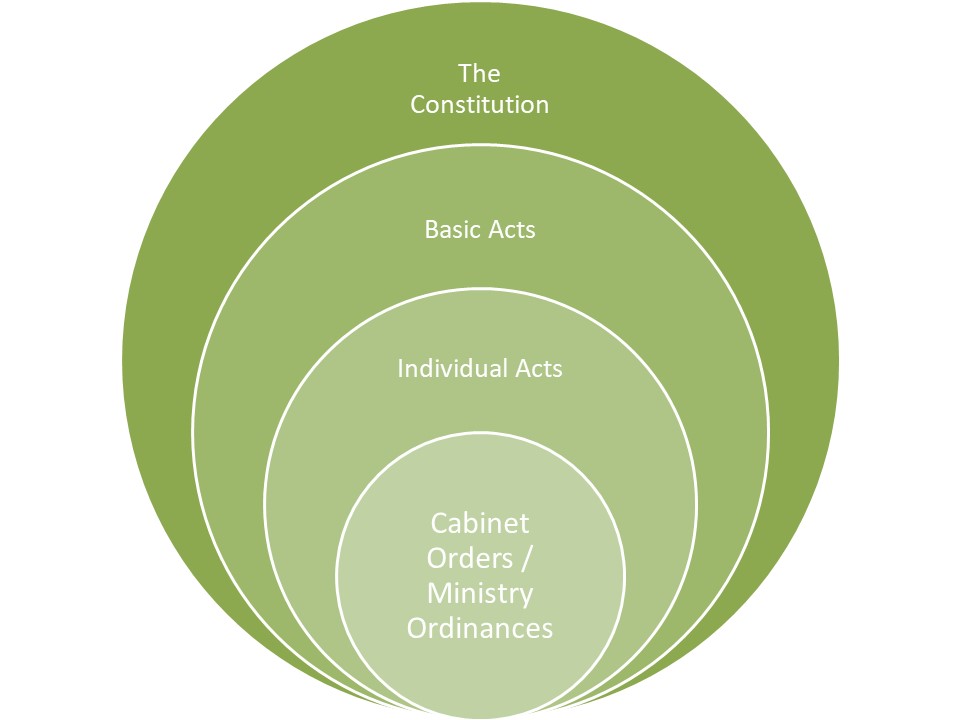

Basic acts are legal standards enacted by the Diet, and in that regard, there is no formal difference between their effects and the effects of individual acts. However, individual acts generally define rights and obligations while basic acts “describe a mentality, and the content of a basic act provides the government with answers in the form of legislative guidelines for legislative bodies and guidelines for interpretation and implementation for executive bodies” (Yamazaki, 2010). Thinking of basic acts in those terms, we can interpret the relationship between different types of laws as follows: basic acts link the Constitution and individual acts, and individual acts link basic acts to cabinet orders and ministry ordinances). In addition, it has been emphasized that “the significance of basic acts as guidelines is demonstrated when they are used to make necessary amendments or revisions to existing individual acts to accommodate for the enactment of basic acts, or when closely reviewing the consistency of basic acts and other such laws when revising individual acts after a basic act has been enacted” (Kawasaki, 2006), so it is understood that basic acts not only affect future individual acts but can affect existing ones as well. Also, from the perspective that basic acts provide guidelines for the creation of future legislation, it could be argued that another merit of basic acts is that they allow for the use of binding power by creating legal obligations and not just by assigning political responsibilities.

Next, we will examine the sorts of roles basic acts have played in society in the past. Professor Eiichi Yamasaki has identified four eras in the history of basic acts. As we will see, there have been various English terms used to name basic acts over the years, but in Japanese, every law mentioned below contains the term “Kihonhou” or one of its abbreviated forms. The first law called a “Kihonhou” was the Fundamental Law of Education, enacted in 1947. Just like the Atomic Energy Basic Act (1955) and other such laws, Prof. Yamasaki says that basic acts from the first era emphasized the clarification of principles or guidelines. The second era began in the 1960s. The basic acts of the second era defined the direction of policies, and “with a backdrop of requests and pressure from related organizations,” the Agricultural Basic Act (1961) is also considered to have provided “a type of legal protection” (Yamasaki, 2010). In addition, the Basic Act on Disaster Management – which was enacted in 1961 in response to a disaster that occurred in 1959, the Isewan Typhoon – was enacted with the intent of combining individual acts on disaster response that were previously fragmented. The third era saw basic acts that responded to social issues that arose during the period of Japan’s rapid economic growth. They aimed to take comprehensive approaches to those issues, as demonstrated by basic acts such as the Basic Law for Environmental Pollution Control (1967) and the Basic Law on Traffic Safety Measures (1970).

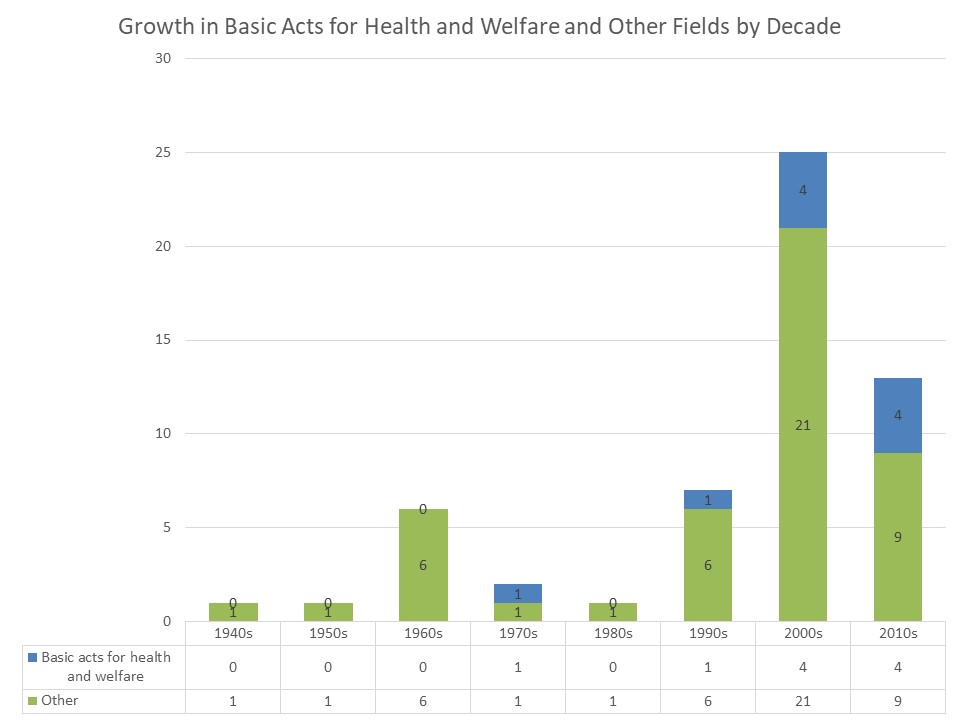

Next is the fourth and current era. This era is characterized by an increase in basic acts that respond to issues arising from the transition of society as it undergoes significant change. They include the Basic Environmental Law (1993), the Basic Act on Measures for the Aging Society (1995), and the Basic Law for a Gender-Equal Society (1999). There have been more basic acts than we have space to mention for the declining birthrate and aging population; technology; the promotion of agriculture, forestry, and fisheries; and various efforts for the economy. There have even been basic acts like the Basic Space Law (2008) and the Basic Act on Sport (2011). As the following chart demonstrates, basic acts have been enacted in greater numbers since the 2000s compared to the postwar period. Japan’s society, culture, and industries have had to face the changing economic circumstances of Japan (such as the period of rapid economic growth or after the bubble economy collapsed) and new technological advances (like the spread of the internet, which is considered the most significant network revolution since the invention of the printing press). It seems safe to say that various basic acts were enacted to help Japan’s society, culture, and industries overcome those changes or the issues arising from them.

Chart 2 – Growth in basic acts for healthcare and welfare and for other fields by decade

*Basic acts were counted using the e-Gov Law Search website provided by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications using the Japanese term “Kihonhou” and its abbreviated forms. Orders for enforcement, cabinet orders, and cabinet office orders were not included. Dates of enactment were derived from law numbers. Additionally, we have decided to include five laws that have expired or have been revised as well as the Basic Law for Child and Maternal Health and Child Development and the unenacted Basic Act On Stroke, Heart Disease and Other Cardiovascular Disease Measures.

When thinking about the Basic Law for Dementia, we must also consider the Basic Act for Persons with Disabilities (1993) which it is modeled on. We also must not overlook the increase in basic acts related to healthcare in recent years. Starting with the Cancer Control Act (2006), other basic acts for healthcare are the Act on Promotion of Resolution of Issues Related to Hansen’s Disease (2008), the Basic Act on Hepatitis Measures (2009), the Basic Plan for Promotion of Measures against Alcohol-related Harm (2013), the Basic Law on Measures against Allergic Diseases (2014), the Basic Law on Measures Against Gambling Addiction (2018), and the Basic Act On Stroke, Heart Disease and Other Cardiovascular Disease Measures (2018). At the time of writing in March 2020, Japan and the entire world are in the middle of confronting an infectious disease called the novel coronavirus or COVID-19, but health policy in recent years has been shifting its focus from infectious diseases to non-communicable diseases (NCDs). One prominent characteristic of NCDs is that People Living With NCDs (PLWNCDs) must live with disease as part of their everyday lives. Healthcare only represents a single aspect of living with an NCD, so to improve quality of life for PLWNCDs, issues from various fields related to everyday living must be addressed.

As the Framework for Promoting Dementia Care makes clear, it is already recognized that dementia is a policy issue that cannot be sufficiently handled only by policies from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, as it was handled in the past. As you know, dementia is included in current healthcare, nursing, and welfare plans such as in the Healthcare Plan or the Long-term Care Insurance Plan, but other fields still lack plans for dementia. Professor Hiroshi Shiono classifies basic acts as targeting (1) awareness-building, (2) policy, (3) legal planning, (4) cross-ministerial measures, and (5) lack of legal standards (such as when content concerning rights and obligations is abstract and penalties are not defined) (Shiono, 2008). Among them, it could be said that (1) awareness-building and (4) cross-ministerial measures are especially important for the Basic Law for Dementia to provide.

In Conclusion

In this column, we examined the positioning of basic acts among administrative laws and past trends in basic acts. After considering the characteristics of dementia as a policy issue and examining the characteristics of basic acts, we can safely say that a basic act is necessary for dementia.

Of course, even if the Basic Law for Dementia or a similar basic act is not enacted, it may be sufficient if “a society in which the dignity of people with dementia is upheld and they are included as full members of society” (from Chapter I of the Basic Law for Dementia) is successfully created. However, as the social contract theory explains, we created civil society by entering into contracts for the common good. As a law-governed country, society in Japan today relies on the law to prevent self-serving decisions or judgments to be made on the whims of single actors so that the common good in civil society can be optimized in a stable and continuous manner.

As discussed in our previous column, it is necessary to create publicness between people that perceive dementia as a private affair and people who have not yet had contact with dementia. Speaking from that perspective, one could argue that the Basic Law for Dementia will create publicness to search for the common good for dementia as a modern policy issue. And, just as we mentioned before, if publicness is to be defined as “something that establishes man-made relationships between multiple differing types of cooperation rather than natural unity and homogeneity based on collective beliefs,” publicness is no more than a mere beginning. However, it is because publicness is the starting line that we cannot have too many expectations.

If it becomes necessary to create a law, there will be a flurry of opinions on various topics addressing everything to the smallest detail. There may be no limit to the amount of topics to discuss. Holding lively discussions is wonderful. However, such discussions could lead to excessive demands for unity and homogeneity in society. Each and every one of us differs in age, gender, position, and way of thinking. The purpose of the Basic Law for Dementia is not to make everyone agree, it is to establish publicness so that people with different opinions have opportunities to pursue the common good.

Lately, we are still living with unfamiliar routines as the novel coronavirus interrupts our daily lives. I think that many people that our entire society is on edge. I think it is best we take a moment to remind ourselves that society was created by people to pursue the common good.

[Reference materials]

Kawasaki, Masaji. 2006. “Rethinking basic acts (Part 3).” Jichi Kenkyu, No81-1, 65-91.

Shiono, Hiroshi. 2008. “On ‘basic acts.’” Transactions of the Japan Academy, No63-1, 1-33.

Nasu, Kosuke. 2005. “The Prototype of Political Thinking: Where Did Policy Studies-Based Thinking Originate?” In Adachi, Yukio, “What is Policy Studies-Based Thinking – Experiments in Public Policy Fundamentals,” Chapter 8. Keiso Shobo Publishing.

Yamasaki, Eiichi. 2010. “On the Draft of the Disaster Recovery and Rehabilitation Basic Act.” Studies in Disaster Recovery and Revitalization, No2, 89-91.

Society for the Study of Legal Terminology. 2012. “Dictionary of Legal Terminology, Fourth Edition.” Yukihaku Publishing.

About the author

Shunichiro Kurita (HGPI Senior Associate; Steering Committee Member, Designing for Dementia Hub)

Top Research & Recommendations Posts

- [Policy Recommendations] Reshaping Japan’s Immunization Policy for Life Course Coverage and Vaccine Equity: Challenges and Prospects for an Era of Prevention and Health Promotion (April 25, 2025)

- [Research Report] Perceptions, Knowledge, Actions and Perspectives of Healthcare Organizations in Japan in Relation to Climate Change and Health: A Cross-Sectional Study (November 13, 2025)

- [Research Report] The 2025 Public Opinion Survey on Healthcare in Japan (March 17, 2025)

- [Research Report] The 2026 Public Opinion Survey on Healthcare in Japan (February 13, 2026)

- [Research Report] 2019 Survey on Healthcare in Japan

- [Research Report] Building a Mental Health Program for Children and Measuring its Effectiveness (June 16, 2022)

- [Policy Recommendations] Developing a National Health and Climate Strategy for Japan (June 26, 2024)

- [Research Report] The Public Opinion Survey on Child-Rearing in Modern Japan (Final Report) (March 4, 2022)

- [Research Report] The 2023 Public Opinion Survey on Satisfaction in Healthcare in Japan and Healthcare Applications of Generative AI (January 11, 2024)

- [Policy Recommendations] Mental Health Project: Recommendations on Three Issues in the Area of Mental Health (July 4, 2025)

![[Registration Open] Online Seminar “Implementing Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) Measures into Society: Towards a Data-Driven Health System” (April 21, 2026)](https://hgpi.org/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/HGPI_20260421_CKDonlineseminar-.png)