[HGPI Policy Column] No. 28 – From the Planetary Health Policy Team, Part 1 – Why We Choose to Take Action for Planetary Health and Some Historical Background

date : 7/20/2022

![[HGPI Policy Column] No. 28 – From the Planetary Health Policy Team, Part 1 – Why We Choose to Take Action for Planetary Health and Some Historical Background](https://hgpi.org/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/column-28-top_r.png)

<Key points>

- Health and Global Policy Institute will begin a project for planetary health in which we will identify issues and share a direction for solutions in this field for all of Japan.

- The concept of planetary health is based on initiatives the global community began to implement around the 1970s for environmental issues like climate change and the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions.

- Starting around 2014 to 2015, the term “planetary health” has been used in the context of “the health hazards humanity will face and countermeasures we must take if we continue to view the Earth in anthropocentric terms.”

Introduction

As the various effects humanity has had on the Earth come back to impact our daily lives and our health, have you ever considered what sorts of actions we should take in the future? To help answer this question, Health and Global Policy Institute (HGPI) has launched an initiative to identify current issues and summarize next actions to respond to the effects that global climate change will have on human health from the perspective of planetary health.

Although people might recognize the importance of working to address global problems like climate change and air pollution, there may be too few opportunities for them to comprehend the relationships between problems at that scale and individuals’ daily lives in an intuitive manner. As many reports from Japan and overseas tell us, global climate change already presents a number of hazards to our health. In 2015, an outbreak of Dengue fever in Tokyo centered around Yoyogi Park resulted in 108 people becoming infected.*1 Dengue fever is an infectious disease contracted from mosquitoes, and its distribution is said to be influenced by global warming.*2 During a heat wave in summer 2021, a record-high temperature of 49.6°C was recorded in Canada. In just a few days, this extreme heat took the lives of several hundred people due to heat stroke.

As we see an increasing number of examples like these that make us feel how changes to the Earth’s systems directly affect our health, each country is starting to launch initiatives aiming to build sustainable relationships between the Earth and humanity. Examining yearly agendas of G7 and G20 meetings, which bring together leading countries for discussions on major worldwide challenges, we see the emergence of themes that emphasize the relationships between the environment and health in the field of atmosphere and the environment, as well approaches like the One Health Approach within the field of healthcare.

Recent years have also seen the gradual spread of domestic and international initiatives for planetary health. At the Government of Japan, an assessment of health risks posed by climate change was included in a 2020 report from the Ministry of the Environment.*3 There is also a growing number of initiatives related to the links between health and the environment from academia and industry. Although industry, Government, academia, and civil society are each engaged in separate efforts for planetary health, nationwide issues have yet to be identified, and a shared national direction has yet to be set. HGPI aims to identify issues for Japan that require a multi-stakeholder response, to deepen understanding for this topic, and to communicate our findings in Japan and abroad while creating opportunities to move forward. In this, our first column on planetary health, we will introduce the background that led to the birth of planetary health as a concept.

Past initiatives for responding to climate change around the world

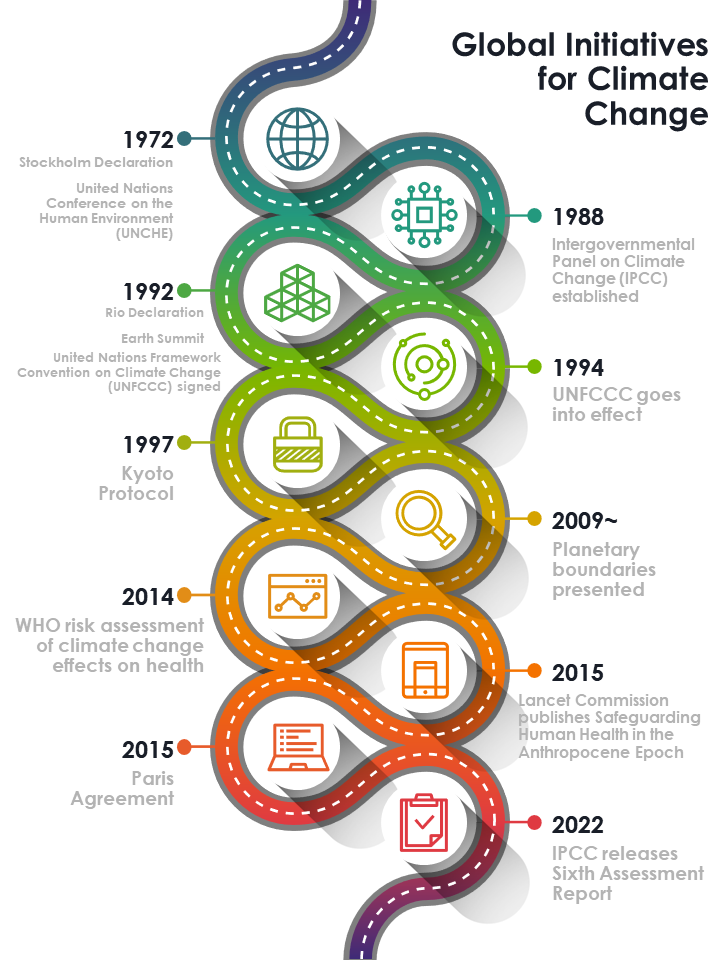

Figure 1: Global initiatives for climate change

A sense of danger toward environmental issues first began to spread during the 1960s, when the economies of developed countries started growing rapidly in the wake of World War II. At the time, action was limited to each country’s domestic efforts undertaken on a per-country basis. Then, in 1972, the UN’s first discussions on environmental issues were held at the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment (UNCHE) in Stockholm. Several years later, in 1988, the UN established the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) with the goal of conducting scientific research on climate change. Then, at the “Earth Summit” (the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, UNCED) which was held in Rio in 1992, the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development was signed and adopted by 154 countries with the objective of expanding the Stockholm Declaration. Together with Agenda 21, which was adopted simultaneously to implement its objectives, the Rio Declaration gave major impetus to national and local governments to draw up concrete action plans for addressing issues facing the environment.

Can we see the limits of humanity’s ability to operate safely on the Earth? Introducing planetary boundaries

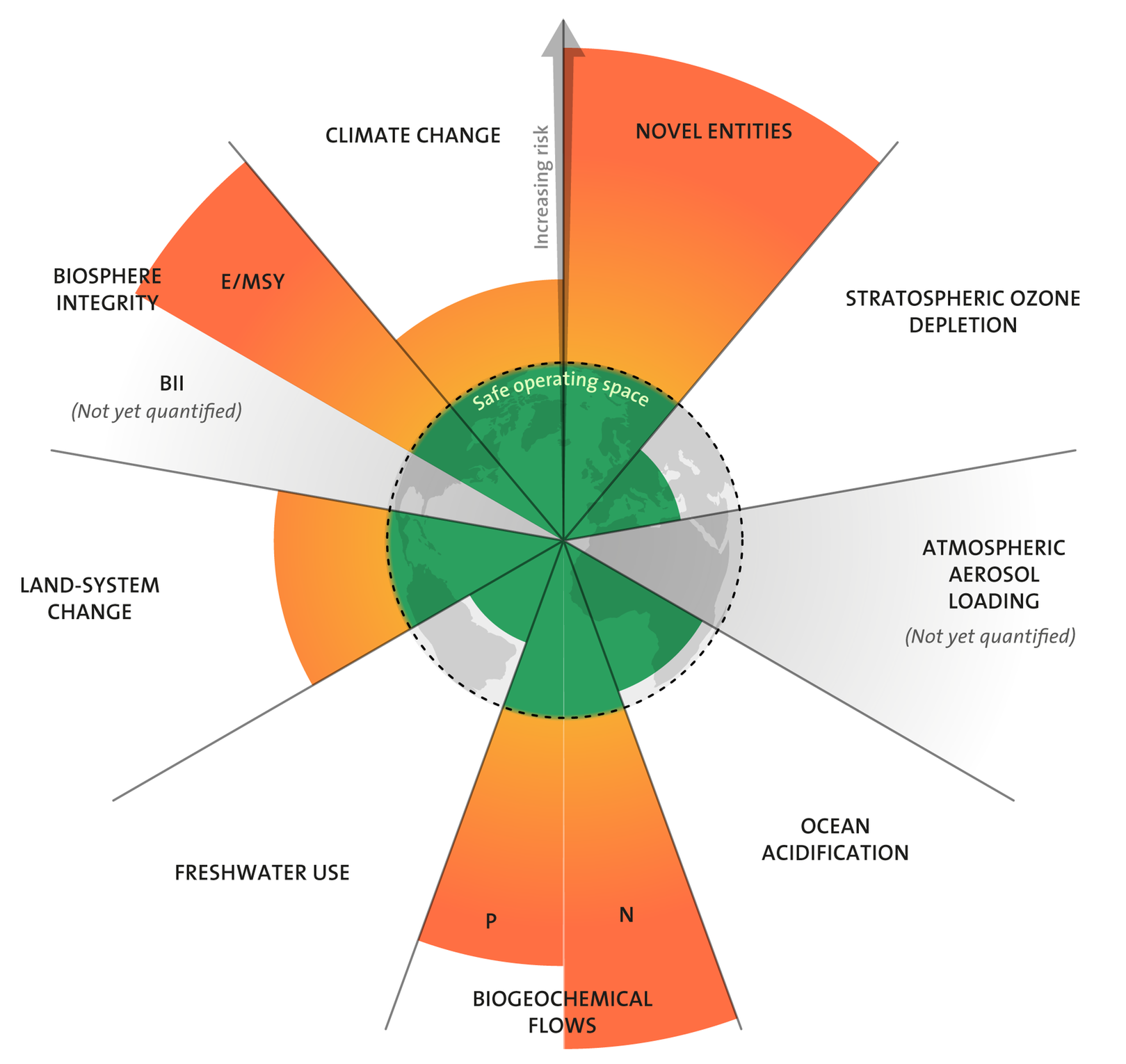

Figure 2. Planetary boundaries (2022)

In 2009, as countries began exploring the links among sustainable societies and the environment, a concept called “planetary boundaries” was described in a report in Ecology & Society.*4 It included a diagram showing the range of safe operating space on Earth for humanity, which has been influential to global movements including the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Planetary boundaries describe upper limits in which humanity can continue developing and prospering over future generations if they go unsurpassed, while surpassing these boundaries carries the risk of rapid or irreversible changes to the environment. They identify the nine most important systems for maintaining our planet’s stability and resilience (its ability to recover naturally) and provide specific thresholds that can be used to assess and verify if boundaries have been crossed in each system. Since they were first presented in 2009, the planetary boundaries have been updated with new names and thresholds for several systems in 2015, 2017, and 2022. Incidentally, the 2022 update (Figure 2) shows five planetary boundaries in which humans can safely operate have already been crossed: climate change, loss of biosphere integrity, altered biogeochemical cycles, land system change, and introduction of novel entities into the biosphere in the form of chemical pollution.

Promoting fair and effective global warming countermeasures with the Paris Agreement

After the conclusion of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), active discussions on effective methods of reducing greenhouse gas emissions have been held around the world. The Kyoto Protocol adopted in 1997 was the first agreement that legally obligated countries to reduce emissions, but its signatories were limited to developed countries. There were lingering challenges due to growing emissions from India and China, which were not included, as well as the withdrawal of the U.S. Later, in 2015, the Paris Agreement was signed or acceded to by all major emitters and included developing countries. Unlike the Kyoto Protocol, which legally obligated its parties to “achieve” target emission levels, the Paris Agreement requires each country to “submit” targets. This means the Paris Agreement takes a bottom-up approach in which all members create and submit their own targets and implement domestic policies, thereby advancing countermeasures for global warming in an effective, equitable manner.

The human health effects of changes to the Earth’s systems is now becoming clear

As global initiatives and analyses of environmental issues like those described above continue to advance, the relationships among changes in the Earth’s systems and human health effects was clearly demonstrated around 2014 to 2015. This has given momentum to the concept of planetary health, in which Earth and human health are viewed as interdependent.

In 2014, the WHO presented its first report on the health impact of climate change.*5 In the scenario in which global warming continues at its current pace without effective measures to cut greenhouse gas emissions, it estimated there will be approximately 250,000 additional deaths per year from 2030 and 2050 compared to the scenario with no global warming. These include 96,000 from undernutrition, 60,000 from malaria, 48,000 from diarrhea, and 38,000 due to heat exposure among elderly people . It identified children in developing countries with particularly poor sanitation as the population most vulnerable to climate change. This report was a key analysis of how various factors caused by climate change will harm human health.

At around the same time that report was released, in 2015, a research team assembled by prestigious medical journal The Lancet and the Rockefeller Foundation published a report titled “Safeguarding Human Health in the Anthropocene Epoch.”*6 It presented the concept that “Human health and civilization depend on the Earth’s natural systems, and we must gather environmental and epidemiological evidence and incorporate it into complex models if we are to understand those systems,”*7 forming the basic concept of planetary health in interdisciplinary terms. This concept of planetary health is said to have increased the prominence of more complex, realistic methods of understanding health and disease as they manifest on our unstable and fragile planet.

The concept of “planetary health” is now expanding from academia and being communicated into various industries, such as when the Economist, one of the most influential international political and economic journals in the world, published a special report on planetary health in 2014.*8

In our second column, we will take a look at global trends from the time the concept of planetary health was formed to today.

References

*1. National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Japan. 2015. “Regarding the Domestic Outbreak of Dengue Fever in Tokyo, Centered Around Yoyogi Park.”

*2. Ministry of the Environment. 2006. “Global Warming and Infectious Disease – What Do We Know Now?”

*3. Ministry of the Environment. 2020. “Regarding the Climate Change Impact Assessment Report.”

*4. Planetary Boundaries. Stockholm Resilience Centre.

*5. WHO. Quantitative Risk Assessment of the Effects of Climate Change on Selected Causes of Death, 2030s and 2050s.

*6. Whitmee, S., Haines, … & Yach, D. 2015. “Safeguarding Human Health in the Anthropocene Epoch: Report of The Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on Planetary Health.” The Lancet, 386 (10007), 1973-2028.

*7. Nagasaki University (Supervised Translation). 2022. “Planetary Health: Protecting Nature to Protect Ourselves.” Maruzen Publishing Co., Ltd.

*8. The Lancet and Rockefeller Foundation. 2014. “Planetary Health.” The Economist.

Column author

- Sayaka Honda (Intern, HGPI)

- Shu Suzuki (Associate, HGPI)

- Joji Sugawara (Senior Manager, HGPI)

HGPI Policy Column (No.27) -from the Dementia Policy Team- >

< HGPI Policy Column (No.29) -from the Planetary Health Policy Team-

Top Research & Recommendations Posts

- [Policy Recommendations] Reshaping Japan’s Immunization Policy for Life Course Coverage and Vaccine Equity: Challenges and Prospects for an Era of Prevention and Health Promotion (April 25, 2025)

- [Research Report] Perceptions, Knowledge, Actions and Perspectives of Healthcare Organizations in Japan in Relation to Climate Change and Health: A Cross-Sectional Study (November 13, 2025)

- [Research Report] The 2025 Public Opinion Survey on Healthcare in Japan (March 17, 2025)

- [Research Report] The 2026 Public Opinion Survey on Healthcare in Japan (February 13, 2026)

- [Research Report] 2019 Survey on Healthcare in Japan

- [Research Report] Building a Mental Health Program for Children and Measuring its Effectiveness (June 16, 2022)

- [Policy Recommendations] Developing a National Health and Climate Strategy for Japan (June 26, 2024)

- [Research Report] The Public Opinion Survey on Child-Rearing in Modern Japan (Final Report) (March 4, 2022)

- [Research Report] The 2023 Public Opinion Survey on Satisfaction in Healthcare in Japan and Healthcare Applications of Generative AI (January 11, 2024)

- [Policy Recommendations] Mental Health Project: Recommendations on Three Issues in the Area of Mental Health (July 4, 2025)

![[Registration Open] Online Seminar “Implementing Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) Measures into Society: Towards a Data-Driven Health System” (April 21, 2026)](https://hgpi.org/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/HGPI_20260421_CKDonlineseminar-.png)