[HGPI Policy Column] No.16 – From the Child Health Team – Child Health Column 1 – The Background of the Formulation and Enactment of the Basic Law for Child and Maternal Health and Development

date : 10/24/2020

Tags: Child Health, HGPI Policy Column

![[HGPI Policy Column] No.16 – From the Child Health Team – Child Health Column 1 – The Background of the Formulation and Enactment of the Basic Law for Child and Maternal Health and Development](https://hgpi.org/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/column-top-childhealth-3.jpg)

In FY2020, child health was added to the Health and Global Policy Institute (HGPI) healthcare policy agenda. Our activities for child health are underway.

The enactment of the Basic Law for Child and Maternal Health and Child Development in December 2019 accelerated efforts to provide seamless healthcare, welfare, and other types of support to all women during pregnancy and throughout the child-rearing process from birth to adulthood. Discussions at the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare’s (MHLW) Council for Child Health and Development began in earnest in February 2020.

Establishing systems that enable all of society to come together to support pregnant women and everyone raising children and ensure good physical and mental health of children is an urgent issue for Japan’s future. Japan faces a host of issues including but not limited to care for both mothers and children during reproduction, the perinatal, and neonatal periods; mental health in puberty; support for children with serious disabilities that require round-the-clock care; abuse; and child poverty and nutrition. In response to current social conditions, HGPI is carrying out survey research, publicizing information, and hosting discussions with stakeholders in Japan and abroad from government, industry, academia, and civil society in our efforts to contribute to child health. We are always accepting applications from those who wish to lend their support or cooperation to this project and ask all interested parties to please contact us.

As one of our activities for this project, we have started publishing a column on child health policy.

Health and Global Policy Institute

Child Health Team

Contact: Yoshimura

For questions, please contact: info@hgpi.org

Child Health Column 1 – The Background of the Formulation and Enactment of the Basic Law for Child and Maternal Health and Development

<Key Points>

• Child growth refers to the process of events from birth to adulthood that span the neonatal period, infancy, childhood, and adolescence.

• The Basic Law for Child and Maternal Health and Child Development is a basic act that aims to allow growing children and their guardians or other related parties to receive the care they need in a seamless manner.

• The Basic Law for Child and Maternal Health and Child Development was enacted with a background of rapidly changing demographics due to a falling birthrate and population aging and vertical segmentation in existing systems for child and maternal health that caused inefficiency and discrepancies in care.

In December 2018, the Basic Law for Child and Maternal Health and Child Development was enacted at a plenary session of the House of Councilors. [1] In this, the first column in our series on child health policy, we will introduce the law and its background as well as take an overhead look at past frameworks for child health in Japan.

Defining “child growth” and “child health and development”

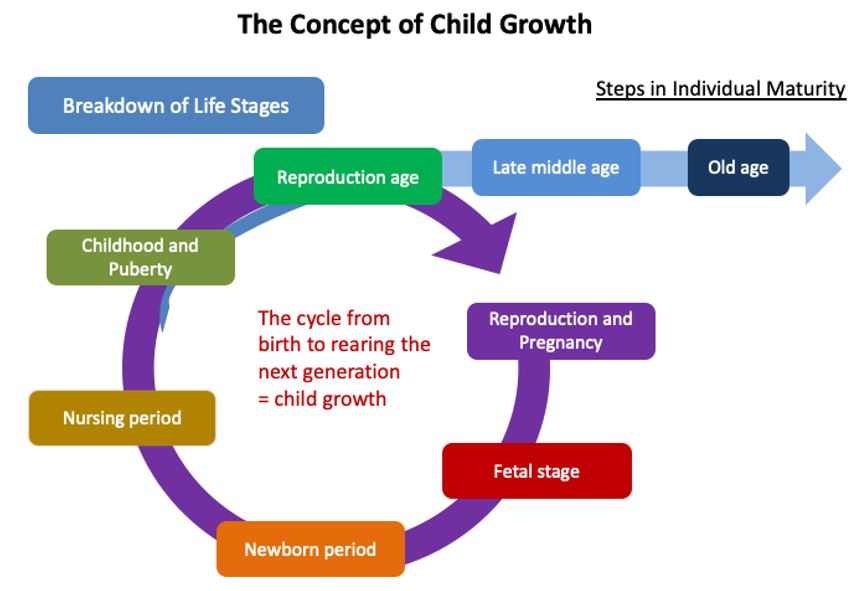

“Child growth” refers to the series of stages of the growth process from birth to adulthood including the neonatal period, infancy, childhood, and adolescence (Figure 1). “Child health and development” refers to providing targeted and comprehensive healthcare for issues related to difficulties during pregnancy, birth, and nursing; and problems or issues that can affect mental and physical health at each stage of the growth process. It also refers to services that are closely related to those topics such as education or welfare services. [2][3]

Figure 1: The Concept of Child Growth

Source: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, “Recent Developments in Legislation for Maternal and Child Health,” March 19, 2019.

The background of the Basic Law for Child and Maternal Health and Child Development

In recognition of the rights of children, an investigative committee at the Japan Pediatrics Association (JPA) started holding discussions in 1991 that focused on the need to establish a legal framework for providing systematic support for society-wide efforts to improve the environment for the healthy growth of children. They advocated for the enactment of such a law at a JPA symposium in 1994, calling their proposed law the “Child Health Act.” They criticized current systems in Japan, a country which is undergoing rapid demographic change due to a decreasing birthrate and population aging, for having a vertical divide among healthcare, health, and welfare systems, insufficient social measures to ensure children grow up in good health, and lagging efforts to establish households, workplaces, and social environments that encourage the healthy growth of children. [4] Recognizing the need to rapidly build systems for providing children support from all of society and creating an environment that encourages the healthy growth of children, they called for the enactment of the Child Health Act to establish a legal system that would encompass healthcare, health, and welfare and form a foundation for child health and healthcare for the children who will support society in the 21st century. They also pointed out that there are regional discrepancies in healthcare provision systems and health and welfare services and made statements concerning the fact that there are problems related to continuity between types of support related to child and maternal health and school health.

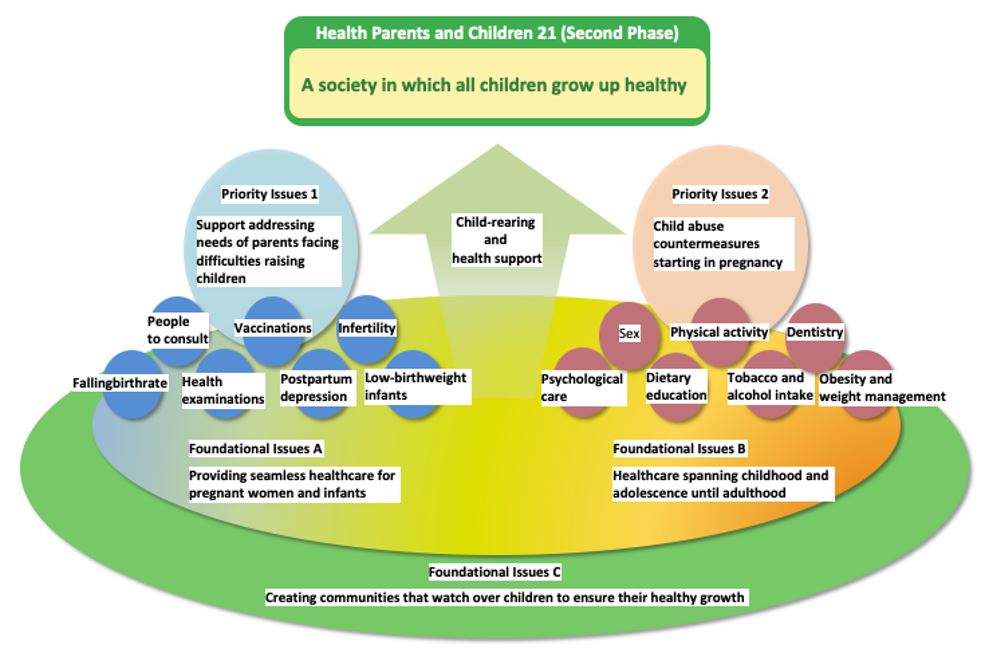

The year 2001 marked the beginning of the first phase of a national campaign called Healthy Parents and Children 21. [5] Healthy Parents and Children 21 is a key component of Health Japan 21and provides a vision for uniting relevant individuals, institutions, and organizations in central efforts for maternal and child health in the 21st century. The first phase of Healthy Parents and Children 21 was a 14-year plan that established four major agenda items: reinforce countermeasures for health issues to promote health education during adolescence; ensure the comfort and safety of mothers during pregnancy and childbirth and provide support for infertility; establish an environment for maintaining and improving health and healthcare standards for children; and promote healthy mental development among children while reducing anxiety towards raising children. Looking at the first phase’s final report, we find that although 80% of approximately 70 indicators showed improvement, two indicators worsened. Namely, the suicide rate for people among their teens increased and the number of low-birthweight infants increased. [6] The second phase of Healthy Parents and Children 21 started in 2015 with goals that are based on the reported results for the first phase. Those goals include providing seamless health measures for pregnant women and infants (particularly mothers having their second or later child) , promoting health measures from school age and adolescence to adulthood, developing communities that watch over the healthy growth of children, providing support for parents facing difficulties raising children, and implementing countermeasures to prevent child abuse starting from pregnancy (Figure 2). The second phase of Healthy Parents and Children 21 is scheduled to end in FY2024.

In this manner, the necessity of a legal framework that eliminates the vertical division in systems for maternal and child health, prevents isolation among people raising children, and creates a society that ensures that all children can grow up in good physical and mental health has been discussed over the course of efforts for improving child health. Creating a society that ensures peace of mind for women during pregnancy and birth and for people in the process of raising children and that enables children to grow up healthy in their communities and in society so they can rear the next generation is a critical issue facing Japan. To reflect this expanded focus to include those other than children and to communicate the belief that support encompassing the entire life cycle from reproduction and pregnancy to the elderly years is necessary, the name of the Child Health Act was revised to the Basic Law for Child and Maternal Health and Child Development. Recognition towards the fact that the creation of a society that ensures seamless support for pregnant women and children over the entire growth process from birth is extremely important for the future of Japan led to the enactment of the Basic Law for Child and Maternal Health and Child Development in December 2018.

Figure 2: Key and Fundamental Issues for the Second Phase of Healthy Parents and Children 21

Source: Healthy Parents and Children 21, http://sukoyaka21.jp/about

[1] MHLW, 2018. “Official Gazette Extra 276.”

[2] MHLW, 1995. “Review Committee Report on the Basic Plan for the Establishment of the National Center for Child Health and Development (Tentative name).”

[3] Itoh, Hiroshi. 1999.”Concept of ‘Seeiku’ and Planning of ‘The National Seeiku Institute.'” IRYO, vol. 53, no. 1, pp. 33-34.

[4] Matsudaira, Takamitsu, 2019. “The 30th Japan Pediatric Association Forum: The Enactment of the Basic Law for Child and Maternal Health and Development and Next Steps.” Retrieved October 10, 2020. https://www.jpa-web.org/dcms_media/other/第30回日本小児科医会総会フォーラムin京都_190611tue.pdf.

[5] MHLW. “Healthy Parents and Children 21 (Second Phase).” Retrieved October 10, 2020. http://sukoyaka21.jp/about.

[6] MHLW, 2013. “Final Evaluation Report on Healthy Parents and Children 21.” Retrieved October 10, 2020. https://www.mhlw.go.jp/file/05-Shingikai-11901000-Koyoukintoujidoukateikyoku-Soumuka/0000030082.pdf.

About the author

Akira Shimabukuro (Intern, HGPI / Master of Public Health (Class of 2021), Harvard. T.H. Chan School of Public Health)

Top Research & Recommendations Posts

- [Research Report] Perceptions, Knowledge, Actions and Perspectives of Healthcare Organizations in Japan in Relation to Climate Change and Health: A Cross-Sectional Study (November 13, 2025)

- [Policy Recommendations] Reshaping Japan’s Immunization Policy for Life Course Coverage and Vaccine Equity: Challenges and Prospects for an Era of Prevention and Health Promotion (April 25, 2025)

- [Research Report] The 2025 Public Opinion Survey on Healthcare in Japan (March 17, 2025)

- [Research Report] The 2026 Public Opinion Survey on Healthcare in Japan (February 13, 2026)

- [Research Report] Building a Mental Health Program for Children and Measuring its Effectiveness (June 16, 2022)

- [Research Report] 2019 Survey on Healthcare in Japan

- [Policy Recommendations] Developing a National Health and Climate Strategy for Japan (June 26, 2024)

- [Policy Recommendations] Mental Health Project: Recommendations on Three Issues in the Area of Mental Health (July 4, 2025)

- [Research Report] The 2023 Public Opinion Survey on Satisfaction in Healthcare in Japan and Healthcare Applications of Generative AI (January 11, 2024)

- [Research Report] The Public Opinion Survey on Child-Rearing in Modern Japan (Final Report) (March 4, 2022)

![[Registration Open] Online Seminar “Implementing Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) Measures into Society: Towards a Data-Driven Health System” (April 21, 2026)](https://hgpi.org/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/HGPI_20260421_CKDonlineseminar-.png)