[Event Report] The 108th HGPI Seminar – At the Forefront of the Debate at COP27: The Climate Crisis and Health (December 5, 2022)

date : 2/1/2023

![[Event Report] The 108th HGPI Seminar – At the Forefront of the Debate at COP27: The Climate Crisis and Health (December 5, 2022)](https://hgpi.org/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/hs108-top_JPNENG-1.jpg)

Health and Global Policy Institute (HGPI) has established an advisory board that will outline an agenda and identify the next steps for Japan from the perspective of planetary health to ensure sustainability for both the Earth and human health. For our 108th HGPI Seminar, we hosted Mr. Yusuke Matsuo, Director of the Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES) Business Task Force, and Professor Masahiro Hashizume, who serves at the Department of Global Health Policy of the Graduate School of Medicine at the University of Tokyo. They talked about discussions held at the frontline of this field at the 27th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP27) and health.

Key points of the lectures

- Climate change will impact human health through various channels, including increased extreme weather events and altered ecosystems caused by warmer weather.

- We must transform our perception of the problem of climate change. Rather than only seeing it as global warming, we must renew our recognition of climate change as a climate crisis and a serious problem facing security and human rights.

- While progress was made in the field of “Loss and Damage” at COP27, issues rooted in conflicts of interest rose to the surface during discussions on how to advance mitigation measures.

- For society (including the health and medical sector) to advance measures for climate change, rather than focusing on concentrated efforts from individuals, we must create policies and systems that deliver solutions.

Why is it a problem if the planet warms by 2°C by the end of the century?

(Professor Hashizume) The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report outlines scenarios for global warming of 2°C (and 4°C) by the end of the century. There are several decades until the end of the century, so how does gradual warming relate to human health? We should take careful note of the following two points.

- Extreme weather events will become more frequent

First, there will be more extreme climate events like torrential rains, flooding, heat waves, and droughts. In addition to being natural disasters, torrential rains and floods can result in secondary hazards to human health. For example, there is data from Bangladesh that shows outbreaks of cholera have occurred after floods. A time series plot of patient visits at a Dhaka City hospital specializing in diarrhea from 1996 to 2003 showed that the number of patients with cholera increased after floods. During the rainy season in 1998, unprecedented rainfall caused river levels to exceed their maximum capacities and over 50% of the capital city of Dhaka was flooded. The unsanitary conditions that occurred as a result led to a cholera epidemic that turned healthcare facilities into field hospitals. Not only did many patients require hospitalization, but the provision of regular medical services was also delayed.

The number of people around the world who are exposed to heat waves is also on the rise. This is not a prediction; this is something that is already happening in every region of the globe. Data on the number of days exposed to heat waves every year for people age 65 years and over (from 1986 to 2005) and the total number of people exposed to heat waves (billion person-days) reveals that person-days of heat wave exposure have increased since the start of the 2010s. The most recent figures show around 3 billion person-days of exposure.

- Ecosystems are sensitive to warming (even more than humans)

Second, ecosystems are more sensitive to warming than humans. This means even increases in temperature that seem modest like 2°C (or 4°C ) by the end of the century will have profound impacts on ecosystems.

Diseases like malaria and dengue fever are called “arthropod-borne diseases.” As temperatures rise, the habitats of the arthropods that carry these diseases may expand beyond their current ranges. For Aedes aegypti (the yellow fever mosquito) and Aedes albopictus (the tiger mosquito), which carry dengue, basic reproduction numbers (an indicator of ease of disease transmission) have recently increased by 7% to 13%. Furthermore, the number of months suitable for malaria transmission (warm months) from 1950 to 2020 increased by 39% in countries where the Human Development Index (HDI) is low and by 15% in countries where the HDI is moderate. In other words, developing countries are facing growing risks of malaria outbreaks.

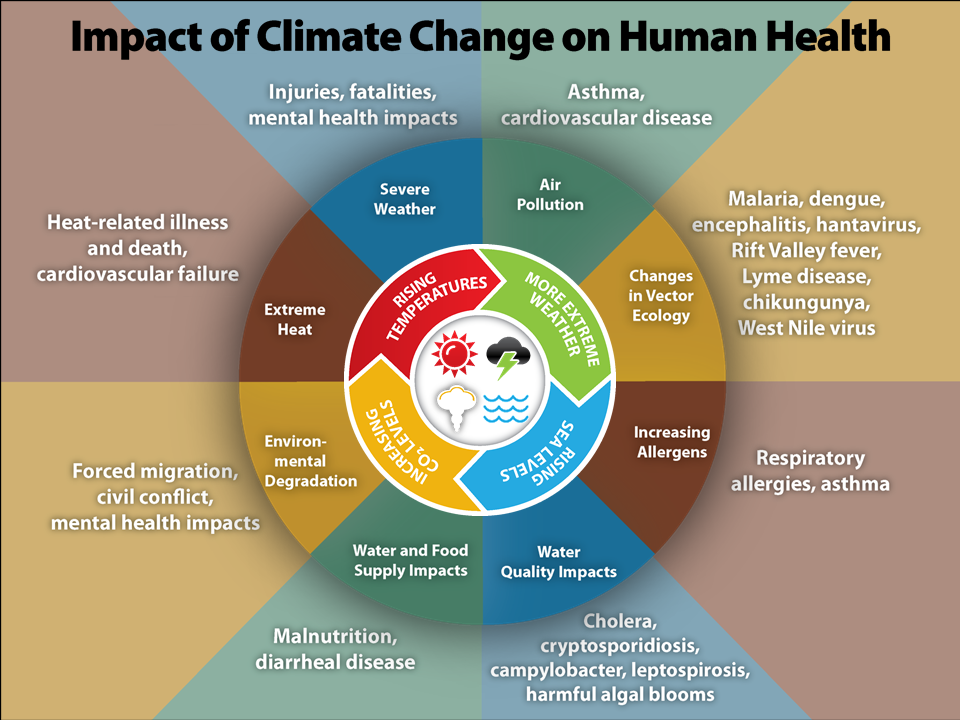

In addition to items 1) and 2) above, climate change is impacting human health through various channels, as shown in Figure 1. Steps to address these impacts on health must be taken through both mitigation and adaptation measures. For details, please refer to Mr. Matsuo’s presentation.

Figure 1

We must recognize climate change within the context of a “climate crisis”

(Mr. Matsuo) For the past ten years or so, I have been working on trying to determine how companies can understand and take action for climate change. Recently, I think the word “health” has become a keyword of great interest within the context of climate change. When attempting to interpret climate change, in addition to knowing about it as a phenomenon, it is also helpful to know its context. Today, it is my sincere hope for you to also learn about that context.

To start, compared to people in other countries, the weight to the words we use to describe this problem is different in Japan. In Japan, we still hear people talk about “Preventing global warming,” or see pictures of the Earth with a face, looking hot and wiping its sweat with a handkerchief. However, in other countries, there is growing recognition of climate change as a serious threat to social stability as well as toward the fact that even though it is too late to stop global warming, we can aim for a “soft landing” before the situation goes too far. A report in a scientific journal called Nature Climate Change said that continued warming could mean the Persian Gulf will reach the threshold of survivability in thirty years, while the medical journal The Lancet notes that “climate change threatens to undermine the past 50 years of gains in public health.” Carbon budget estimates and other projections suggest that limiting warming to 1.5°C will be important for making a “soft landing.” Conversely, it has also been pointed out that exceeding 1.5°C in warming will cause multiple factors to exceed their tipping points, which may lead to cascading, irreversible consequences.

In addition, it is becoming more common for discussions on climate change to encompass a human rights perspective. Dr. Tetsu Nakamura, a physician and member of the Peshawar-kai, has stated that Afghanistan, where he has provided assistance for many years, is experiencing severe droughts more frequently and that “Climate change has destroyed communities and livelihoods.” Former UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Mrs. Mary Robinson has also spoken on the issue, saying, “I was very struck by the fact that the impacts of climate change are undermining a whole range of human rights: rights to food, safe water, and health and education.” Turning our attention outside of Japan, we see that climate change is no longer just an issue that concerns the environment. Rather, we see that it is also one of the greatest humanitarian issues alongside immigrants, refugees, and security.

COP27 discussion points and outcome: Loss and Damage

The two main discussion points at COP27 in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt in November 2022 are described below.

- Responding to climate damage in developing countries (“Loss and Damage”)

Despite the fact that CO2 emissions from developing countries are usually less than those of developed countries, residents of poorer, developing countries are often the ones who suffer due to climate change. In recent years, progress has been made in discussions under the theme of “Loss and Damage” to achieve “Climate Justice,” which aims to eliminate this inequity. In the “Loss and Damage” policy, discussions are being held on providing technical and financial assistance and compensation for the loss and damage that will be impossible to avoid even after mitigation and adaptation measures are implemented. For example, Japan emits about as much CO2 as 55 countries in Africa, and per capita emissions in Japan are eight times greater than average per capita emissions in Africa. For many years, developed countries have refused to enter talks on negotiation for financial cooperation that developing countries are requesting. At COP27, for the first time, developed countries reached an agreement to establish a new fund that will provide financial assistance to developing countries for damage that is clearly being caused by the adverse effects of climate change. In response to this, some have described COP27 as “historic” or “groundbreaking,” saying “We have finally achieved climate justice.” This decision may have been brought about in part due to reports on the health hazards caused by heavy flooding and heat waves.

- Reinforcing efforts to reduce emissions and achieve the 1.5°C target

There are reports that say current targets in each country will not be enough to limit warming to 1.5°C and will result in temperatures increasing from 2.4°C to 2.6°C. Based on that, discussions at COP27 focused on items meant to close the gap between current targets and those required to meet the 1.5°C target, such as increasing emission reduction targets for developing countries, ensuring global emissions peak by 2025, and reaching a global agreement to reduce the use of fossil fuels. Looking at the outcome, however, major emitters like China and India did not increase reduction targets and there was no major progress in strengthening global cooperation on coal reduction and similar measures.

One factor that influenced the outcome of COP27 was large-scale lobbying activities. COP27 was attended by over 600 representatives from the fossil fuel industry, which is 25% more than last year and the most ever. Commenting on this, some youth delegates said lobbying from the fossil fuel industry distorted the outcome of COP27 and called for the establishment of mechanisms to prevent such conflicts of interest. During COP27, there was also an urgent call for participants to sign an open letter on upholding the 1.5°C target without giving in to lobbying from the fossil fuel industry. In the past, lobbying mostly happened in the shadows, but at COP27, it was conducted out in the open. We can take this as a sign that measures to address climate change are viewed, for better or for worse, as a key topic for those in related industries.

Other topics of interest related to health that drew great attention included the Health Pavilion hosted by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Wellcome Trust, which featured a keynote lecture titled “The missing link: Understanding the intersection of climate and health.” A committee from the medical journal The Lancet (which publishes a special issue on the relationship between the climate and health every year) said, “Climate change is the greatest global health threat of the 21st century” and described various health impacts caused by heat waves such as heart disease, impacts on infants and elderly people, more cases of dengue fever, greater food insecurity, and worse nutrition. During a dialogue involving a Japanese industrial group and the Lancet Commission which Mr. Matsuo served as secretary-general, it was pointed out that there is low awareness toward climate change and health-related initiatives in Asia, including in Japan. As one method of addressing this issue, it was suggested that it will be important to involve the Prime Minister’s office and local governments in formulating policies to overcome the siloed manner in which discussions are split among related ministries and agencies.

Why is it difficult to take action against climate change?

There are two main reasons it is difficult to combat climate change. The first is that its impacts are spread out among different times and different places. Since we cannot yet see the future impacts of climate change, and because those impacts will affect developing countries where we may not see them, it is difficult to get a real sense that we must alter our behaviors now. This makes it difficult for people to engage with the problem of climate change as a personal issue. The second is the problem of external diseconomies and public goods. It is currently free to emit CO2, but reducing emissions carries a cost. This means that with our current system, the people who implement countermeasures bear the costs, and all of society gets to benefit. The problem is many free riders only enjoy benefits without bearing any costs. The nature of this problem means that efforts on the individual level – which we are often told to make – will be insufficient. What we require is policies and systems. At the same time, because introducing policies also requires support from each industry and public consensus (as well as awareness of the matter), it is significant that we continue to speak up.

We are also seeing signs of change in Japan. For example, a research team from the Tokyo Medical and Dental University published a study analyzing the impact of warmer temperatures on diabetes risk, and the Liberal Democratic Party’s Parliamentary Association for Heat Stroke Prevention has issued recommendations on preparing for the health impacts of global warming. In any case, climate change will have a certain degree of impact on human health. In terms of both impact and solutions, the health and medical sectors have key roles to play in combating climate change. What we need is a speedy shift in policy.

[Event Overview]

- Speakers:

Mr. Yusuke Matsuo (Director, Business Task Force, Institute for Global Environmental Strategies)

Prof. Masahiro Hashizume (Professor, Department of Global Health Policy, Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Tokyo) - Date & Time: Monday, December 5, 2022; 19:00-20:30 JST

- Format: Online (Zoom Webinar)

- Language: Japanese

- Participation Fee: Free

- Capacity: 500

■Speaker Profiles:

Mr. Yusuke Matsuo (Director, Business Task Force, Institute for Global Environmental Strategies)

After Mr. Yusuke Matsuo worked at Sanwa Bank as a financial advisor specializing in Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) investing, he assumed his current position in 2005. He holds a Master’s degree in Environmental Management and Policy from the Lund University International Institute for Industrial Environmental Economics (IIIEE). He has been continuously engaged in research and activities under the theme of climate change and industry. He is currently Executive Director of the Japan Climate Leaders’ Partnership (JCLP), and serves as an advisor to global companies. His rewards include the Kaya Award from the Japan Society of Energy and Resources (2010) and “Best Environmental Policy Proposal from an NPO or Company” from the Ministry of the Environment. He is the author of Corporate Management in an Era of Changing Climate, published by Nikkei Business Publications, Inc.

Prof. Masahiro Hashizume (Professor, Department of Global Health Policy, Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Tokyo)

Professor Masahiro Hashizume is a physician and an environmental epidemiologist with research interests in climate change and human health, especially in current impacts, future projections, adaptation strategies, and health co-benefits of mitigation policies. He had his residency training in pediatrics in Tokyo, then received MSc in Environmental Health and Policy from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) and a Ph.D. from the Univ. of London (LSHTM). Prof. Hashizume is currently a lead author of the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report and serves as a member of the WHO Technical Advisory Groups on Global Air Pollution and Health and Climate Change and Environment.

Top Research & Recommendations Posts

- [Policy Recommendations] Reshaping Japan’s Immunization Policy for Life Course Coverage and Vaccine Equity: Challenges and Prospects for an Era of Prevention and Health Promotion (April 25, 2025)

- [Research Report] Perceptions, Knowledge, Actions and Perspectives of Healthcare Organizations in Japan in Relation to Climate Change and Health: A Cross-Sectional Study (November 13, 2025)

- [Research Report] The 2025 Public Opinion Survey on Healthcare in Japan (March 17, 2025)

- [Research Report] The 2026 Public Opinion Survey on Healthcare in Japan (February 13, 2026)

- [Research Report] 2019 Survey on Healthcare in Japan

- [Research Report] Building a Mental Health Program for Children and Measuring its Effectiveness (June 16, 2022)

- [Research Report] The Public Opinion Survey on Child-Rearing in Modern Japan (Final Report) (March 4, 2022)

- [Policy Recommendations] Developing a National Health and Climate Strategy for Japan (June 26, 2024)

- [Research Report] The 2023 Public Opinion Survey on Satisfaction in Healthcare in Japan and Healthcare Applications of Generative AI (January 11, 2024)

- [Policy Recommendations] Mental Health Project: Recommendations on Three Issues in the Area of Mental Health (July 4, 2025)

![[Registration Open] Online Seminar “Implementing Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) Measures into Society: Towards a Data-Driven Health System” (April 21, 2026)](https://hgpi.org/en/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/HGPI_20260421_CKDonlineseminar-.png)